KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Fla.—The launch window for one of the most expensive robotic space missions in NASA’s history opens one year from Tuesday. Coming in at $5 billion, Europa Clipper will try to help scientists answer a bold question commensurate with its eye-popping cost: Are there places below the surface of Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, that could support life?

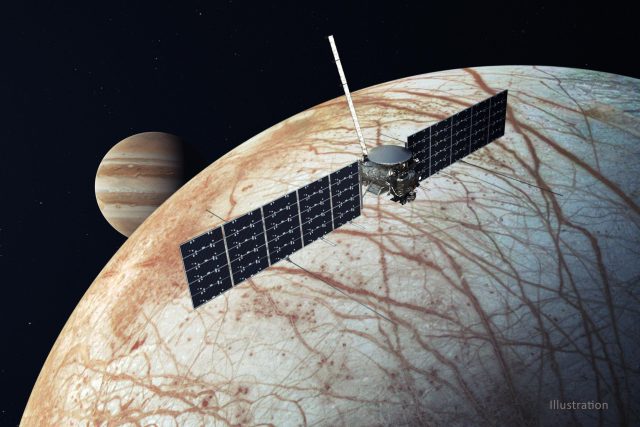

Europa is slightly smaller than Earth’s Moon, and is significantly more interesting to scientists searching for life. The icy world harbors a vast global ocean of liquid water underneath a frozen crust. Clipper will sail past Europa nearly 50 times, coming as close as 16 miles (25 kilometers) from its icy surface to interrogate the moon with a sophisticated suite of nine instruments.

Jordan Evans, who leads the team developing Europa Clipper at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, told Ars on Tuesday the mission is on track to depart for Jupiter during a 21-day planetary launch window opening on October 10, 2024.

The engineers who map out intricate interplanetary trajectories have even determined exactly when Europa Clipper needs to launch. If it flies on the first day of the launch window, liftoff will occur at 11:51 am EDT, according to Evans. That could be slightly adjusted as navigators refine the mission’s trajectory.

“It’s a 6,000-kilogram [13,000-pound] spacecraft with 100-foot [30-meter] wingspan solar arrays, with sensitive radar instruments on them, where all instruments have to operate simultaneously,” Evans said. “So it’s a beast.”

Evans spoke with Ars on Tuesday at the Kennedy Space Center, Europa Clipper’s launch site, almost exactly one year, to the minute, before the mission’s targeted liftoff time. Evans is at the site this week, familiarizing himself with SpaceX’s operations as the company readies for the launch of a Falcon Heavy with NASA’s Psyche asteroid mission.

“Clipper is doing great,” Evans said, while acknowledging the mission has gone through its share of struggles.

Managers had to overcome staffing issues at JPL, which developed Europa Clipper in parallel with at least four other major missions. Then, a political battle was waged over which rocket would send Clipper into the Solar System. NASA officials finally ruled out launching Clipper on the Space Launch System after engineers discovered the spacecraft could be damaged by vibrations induced by the rocket’s solid-fueled boosters.

In 2021, NASA selected SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy for the job. The decision saved an estimated $2 billion, and some novel trajectory design allowed Europa Clipper to take a more direct route toward Jupiter than originally thought possible with a launch on a commercial rocket. That means Clipper will enter orbit around Jupiter in 2030.

The pandemic also threw a wrench into the mission. Delivery dates slipped for some of Clipper’s science instruments as they encountered technical snags. But Evans said Tuesday that technicians assembling Clipper at JPL recently installed the final components needed for the spacecraft to start a final round of tests before shipment from the California lab to the launch site in Florida next May.

Those final additions included all but one of the mission’s science instruments, a suite of cameras, spectrometers, and magnetometers to image Europa and measure the detailed composition of its icy shell. Clipper’s electronics vault, an armored box to shield computers from the damaging radiation at Jupiter, was also recently installed on the main body of the spacecraft, along with a high-gain communications antenna to transmit data back to Earth.

“At launch minus one year, we have taken the flight vehicle through all of its paces,” Evans said. “We’ve simulated launch, we’ve simulated trajectory correction maneuvers, Jupiter orbit insertion, and flybys of Europa with all the instruments operating on the flight hardware and software. The system performed great.”

Testing on tap

Later this month, Clipper’s ground team at JPL will move the spacecraft into a test chamber to blast it with sound, mimicking the acoustic environment it will have to withstand during launch. They will also put Clipper through vibration and shock testing to see how the craft responds to the shaking of a rocket flight.

Then comes an electromagnetic compatibility test, a milestone to ensure all of the electronics aboard Clipper can operate together as designed. Around the end of the year, engineers will transfer the spacecraft into a thermal vacuum chamber to subject it to the extreme hot and cold temperature swings it will see in space.

Some of the tests still to come for Clipper will be simulations to check the spacecraft’s response to problems. Can the spacecraft detect, diagnose, and protect itself against the glitches that could crop up during its mission?

“From here on out, it’s all system-level testing to ensure that any flaws that got into that vehicle—because it is the work of human hands—that we can find them and correct them, if necessary, before we get to launch one year from today,” Evans said.

After transporting the spacecraft across the country to Florida, Clipper’s engineers will install the spacecraft’s European-built solar arrays. Antennas for the mission’s radar instrument will be mounted on the deployable solar panels. This radar package will measure the thickness of Europa’s global ice sheet, and study the internal structure of the icy crust, perhaps finding pockets of liquid water that connect the surface with the ocean below.

The radar is one of the instruments that sets Clipper apart from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which gathered much of the information we know about Europa during its mission at Jupiter more than 20 years ago. Mission managers decided to install the solar panels and radar antennas at the launch site, rather than at JPL, as a hedge against delays in delivering those elements.

“There are always schedule risks,” Evans said. “The team knows we’ve got a lot still ahead of us, but we definitely have ample schedule margin (for launch next October).”