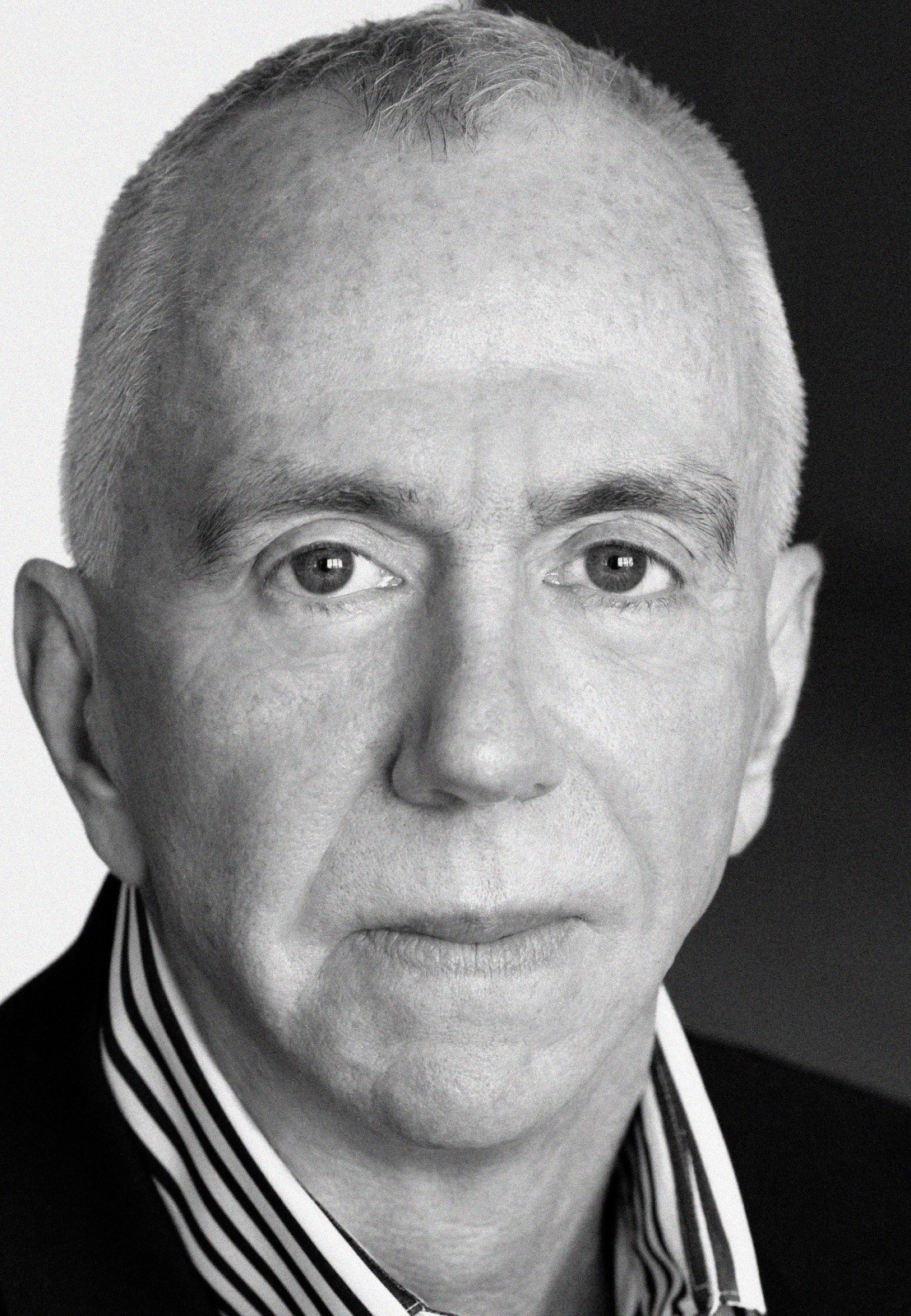

The murder of art dealer Brent Sikkema in Rio de Janeiro on January 15 shocked the art world.

Sikkema, 75, was found stabbed to death in his home in the affluent neighborhood of Jardim Botânico; jewelry and cash were missing. Several days later, police arrested a suspect described in the Brazilian press as a handyman who used to work for Sikkema and his husband, Daniel, who were in the middle of a divorce and have a 12-year-old son.

It was a tragic end for a man who spent decades building bridges between the art worlds of North and South America, who loved Brazil, and who was in the process of applying for residency in the country. In two days, he was set to fly to New York to attend a memorial service for artist Kara Walker’s father, artist and educator Larry Walker, who died over the holidays.

“Mourning not one but two of the most important men who supported and defended me and my art,” Walker, whose career was launched by Sikkema in the late 1990s, wrote in an Instagram post. “Well, it’s too much.”

Kara Walker attends a reception at New York’s Museum of Modern Art on June 29, 2010. Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images.

Those who knew Sikkema remembered him as “generous,” “curious,” “sharp,” and “witty.” He was “a culture vulture” who traveled to Paris and the Bayreuth Festival to hear opera, a man of “impeccable taste,” whose Chelsea apartment once graced the cover of Elle Decor.

He had come a long way from his childhood in a working-class family in rural Illinois. After getting an MFA in photography from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1972, he exhibited at a handful of regional spaces and received a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

In 1976, Sikkema became a director of the Vision Gallery in Boston, which specialized in photography, taking over as its owner in 1980 and running it until 1989. He then moved to New York, where he briefly had a photography gallery. In 1991, he found a space for a small gallery on Wooster Street across from the Drawing Center.

Around that time, Sikkema met Michael Jenkins, an emerging artist whose drawing he bought from a group show at Jay Gorney Modern Art. Sikkema and Jenkins discovered that they had a lot of mutual friends, including artist and critic Jan Avgikos, who suggested the name for Sikkema’s first gallery: Wooster Gardens.

“So typical of Brent,” Jenkins said by phone this week. “He was about to open and he still didn’t have a name. He didn’t want to put his name on the gallery.”

In 1996, Jenkins, who had a two-person show at Wooster Gardens, convinced Sikkema to give him a job at the gallery. (He had a day job that he hated in the graphics department of JPMorgan.)

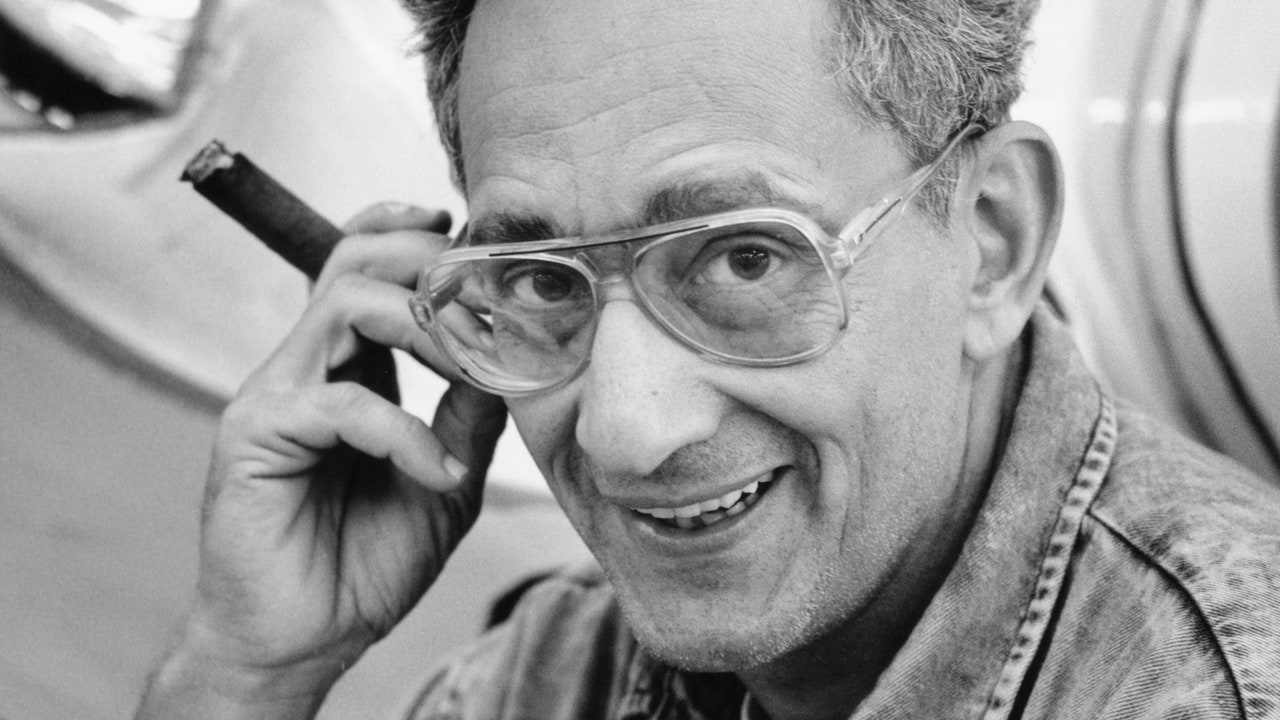

By that time, Sikkema had already met Walker and Brazilian artist Vik Muniz, laying the foundation for what would become the beloved and well-respected gallery known today as Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

The gallery moved to Chelsea in 1999, renting a space on West 22nd Street that it later expanded to 10,000 square feet, four times its original size. Jenkins, who handled day-to-day operations, became a partner in 2003.

“Brent was never managing the gallery,” Jenkins said. “He was always a good cop. He didn’t fire anyone. He didn’t have any tough conversations with anyone. I was stuck with that.”

In recent years, Sikkema was seen at the gallery less and less. He was mulling retirement and preferred to travel the world, seeing his artists where they lived and worked.

Meg Malloy joined the gallery around 2002 and has been a partner since 2005. The three principals were planning to reflect her growing role by updating the gallery’s name to Sikkema, Malloy, Jenkins.

Unlike many of their peers, the Sikkema Jenkins & Co. team didn’t expand beyond New York. Despite that, the venture thrived. While some artists left, many, including Walker and Muniz, remained loyal.

Brazilian artist Vik Muniz is seen with his work made of trash, portraying the sugar loaf in Rio de Janeiro. Courtesy Getty Images.

“We often talked about the scale of the art world and how it forced people to participate in this system that no one likes but that no one knows how to get out of,” said Jerry Saltz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning senior art critic for New York magazine. “We talked about how artists leave galleries; we talked about his totally immovable decision never to go global or be mega.”

That decision was reached after much soul-searching, Jenkins said. Opening in Los Angeles was on the table, but the partners ultimately decided against it.

“I didn’t want to live on the airplane and I knew Brent wouldn’t be doing that,” Jenkins said. “We focused on what we did well.”

The gallery gained a reputation for being rigorous and artist-driven. Its roster was diverse before diversity became an imperative for many dealers. In addition to Walker and Muniz, the gallery represented important Black artists like Mark Bradford, Leonardo Drew, and Deana Lawson. It has been working with 89-year-old Sheila Hicks since 2012 and recently signed emerging stars like Jennifer Packer and Louis Fratino. Jeffrey Gibson, who this year will become the first Indigenous artist to represent the U.S. solo at the Venice Biennale, joined the gallery in 2018.

Art dealer Brent Sikkema (center) with Josephine Halvorson (left) and Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, in Havana, Cuba, in 2019. Courtesy: Josephine Halvorson

“The range of practices and identities, the cultural points of reference, which reflected in the program, are astounding,” said painter Josephine Halvorson, who’s been represented by the gallery since 2011. “They were supporting women artists, queer artists, artists of color. There was no press release to accompany those decisions. There was no financial incentive.”

Artists had carte blanche to follow their dreams, even if it led them into a dead end. The two artists-turned-dealers believed that “art has its own time and its own pace, and it doesn’t necessarily match up with art-fair schedules,” Halvorson said.

Artist Arturo Herrera recalled insisting on a dense installation of 45 unframed works on paper that turned the gallery into a forest-like environment for a 2006 show. Sikkema and Jenkins suggested that it would be too overwhelming for the viewers but went along with Herrera’s vision.

“It was like they said,” Herrera recalled this week. “The audience couldn’t focus.” This was an important learning experience for the artist, who is known for his monumental wall paintings and mixed media works. “It was a great stepping stone,” he said.

Sikkema knew how to solve problems for artists in a way that didn’t make them feel foolish.

When Sikkema visited Halvorson, a professor of painting at Boston University, in 2019, they spoke about her preoccupation with the edges of her pieces. Typically, Halvorson works on a small and medium scale, and Sikkema had a suggestion: Why not just make a really big painting?

“It was so simple and so true,” said Halvorson. “There was something both very caring about this suggestion, but also critical, and funny. We both paused and then started laughing.”

Sikkema’s sense of humor was notorious.

“He was sardonic and had the darkest sense of humor,” said Sascha Feldman, a director at New York’s James Cohan gallery, who worked at Sikkema Jenkins for 10 years. “He liked things that were operatic, dramatic, and bombastic. He loved the wild crazy story.”

“If there was something tense or awkward he’d use a joke to disarm it,” Jenkins said. “He wasn’t a confrontational person with staff and artists. I worked with him for 28 years and we never had a fight. He never came in yelling at anyone.”

Latin America was central to Sikkema’s life, and his gallery.

He had been going to Cuba for years, despite various restrictions on Americans. His friendship with Muniz brought him to Brazil. Over the years, he became friends with the artist’s wife and parents and bought the house where he died.

“Being from Illinois and growing up on a farm, this other side of the world was fascinating to him,” said Herrera, who was born in Venezuela and lives in Berlin. “Its music, architecture, people, language. He was just caught up in this. Some of his best artists were from there and he continued this very direct relation with Latin America, trying to explore, to go there more often, stay longer, get to its core.”

Despite remaining staunchly a New York gallerist, Sikkema cultivated connections with other regions and countries—and across disciplines.

A photograph by Brent Sikkema from a Rio beach. Courtesy: Meg Malloy

“Brent was like an ambassador,” said painter Amy Sillman, who showed with Sikkema Jenkins for about 20 years. “He went out of our bubble, our New York and North American bubble.”

Sikkema was also philanthropic, giving parts of his photography collection and other artworks to the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa, and the Harvard Art Museums. He held fundraising events for a dance residency and LGBTQ nonprofits at his house on Fire Island.

“He was a bridge,” said Sillman, “His life stretched across different lifestyles and awareness.”

His own lifestyle was one of cultivated sophistication. In 2007, he bought a three-bedroom condo at the Heywood, a converted former printing plant in Chelsea, where he regularly hosted soirees after openings. It was filled with mid-century furniture and works by the gallery’s artists.

“I wanted to ask about every object,” Herrera said. “You knew that the chairs you were sitting on, the tables, and the ceramics were carefully selected for the overall aesthetic statement. Everything was done right.”

Sikkema’s life was cut short as he was ready to embark on a new chapter. In December, the dealer went to Brazil for what he thought would be a long visit, planning to stay through the end of the Carnival celebrations in February. He had just completed the purchase of a beach condo and was preparing to move in, Jenkins said. He spent Christmas with Muniz and his family.

“When I talked to him on the phone, he was so obviously content,” Malloy said. “He sent me a beautiful picture of a Rio sunset from the beach and said he was trying to go and meditate there every night.”

After the beach, Sikkema would return to his restored 19th-century townhouse in Jardims Botanica.

Galerie Lelong vice president Mary Sabbatino, a fellow early champion of Latin American art, remembers seeing him at the house while visiting her friends next door, during a visit to Rio.

“I have a strong memory of him framed within the window in beautiful light and smiling at us as we went by,” she said. “It was like a Vermeer.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.