The 2000 psychological horror film American Psycho, directed by Mary Harron and based on the 1991 novel by Bret Easton Ellis, stars Christian Bale as the titular psychopath: a New York investment banker by the name of Patrick Bateman, who moonlights as a serial killer. With a $7 million budget, the sendup of 1980s yuppie culture grossed over $34 million and has become a cult favorite. Some of the canonical artworks of the period, which satirize its individualist culture and brazen excess, make a brief appearance in the film.

Bateman’s career as a killer starts after the legendary scene in which he and his colleagues compare business cards and he finds his own to be lacking. His second murder comes after a colleague is able to get dinner reservations at a hot new restaurant. In a scene that would make anyone cringe, Bateman invites said colleague to his apartment and proceeds to gets him liquored up while playing Huey Lewis and the News, expounding on how great the band is, and murdering him. Things only get bloodier from there.

Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman in American Psycho (2000). Photo: Screen grab.

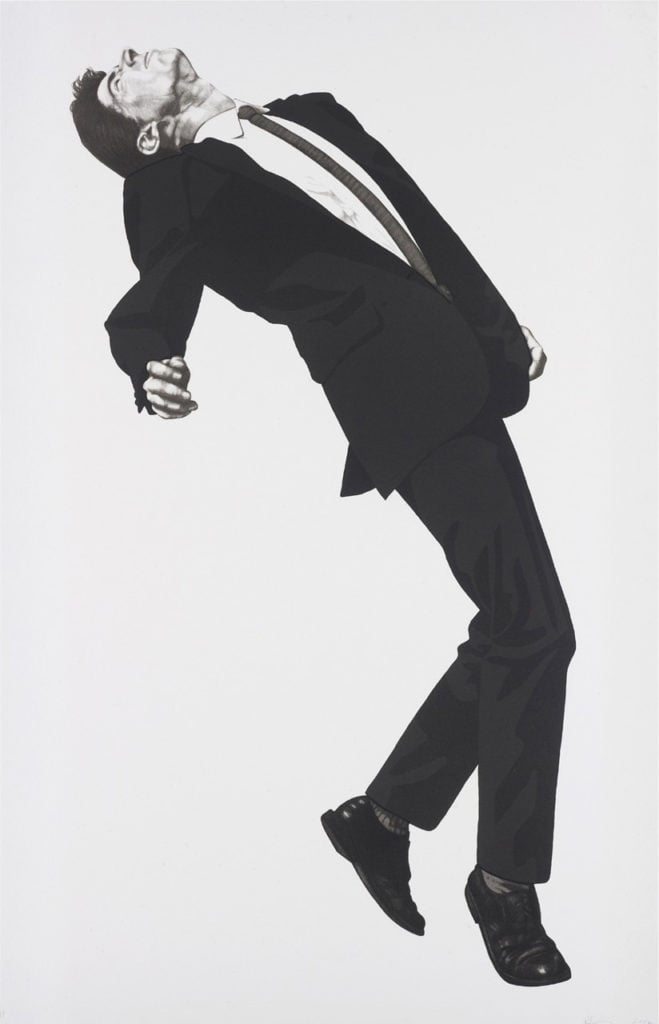

Hanging in Bateman’s apartment are some of Longo’s black-and-white images of men (and women, incidentally) clad in office clothes and assuming contorted poses against white voids. They are perhaps the best-known works by Longo, who emerged in 1977 after his inclusion in the historic “Pictures” show at Artists Space in New York, making him a prominent figure in the Pictures Generation. The “Men in the Cities” drawings were unveiled at his first solo show, at New York gallery Metro Pictures in 1980. Besides a notable career as a fine artist, he has gone on to contribute to culture in many forms, including music videos like R.E.M.’s “The One I Love” (1987) and the 1995 feature film Johnny Mnemonic.

Robert Longo, Jules (2002). Courtesy of Carroll Art.

How do Longo’s works fit in to American Psycho? For one thing, the artist created the series by inviting his models onto rooftops and throwing objects at them, opening the shutter to capture their tortured poses as they dodge the projectiles. Their twisted bodies are a perfect analogue to Bateman’s twisted mind.

What’s more, as the Buffalo AKG Art Museum pointed out, these works were “inspired, in part, by films featuring death scenes that involve a high impact, causing bodies to jerk in dramatic ways.”

The specter of death hanging over them makes them perfect props for a movie with such a high body count.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.