On February 21st, Turkey’s first-ever domestically built fighter jet took to the skies for the first time. It departed from Mürted Airfield Command, located 22 miles north of the capital Ankara. At the controls was Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) test pilot Barbaros Demirbas.

For 13 minutes, the prototype jet cautiously flew (with its landing gear locked down) out to 8,000 feet high and no faster than 265 miles per hour, accompanied by a Turkish Air Force two-seat F-16D fighter.

Then, Kaan circled back around and executed a drag-chute assisted landing at Mürted (formerly Akinci Air Base, before it was renamed due to the participation of local F-16 squadrons in a failed 2016 military coup). Subsequent tests will involve progressively higher altitudes and speed to a peak of around twice the speed of sound.

Kaan plays a key role in Turkey’s plans to eventually develop a self-sufficient military, despite the high costs and technical complexity intrinsic to building modern warplanes.

The twin engine-jet, also known as the National Combat Aircraft (MMU) had its public roll out and initial tax-testing in March of 2023. That year it underwent wind tunnel, radar cross-section, and ejection seat testing—the facilities for which reflected major new investments by TAI. However, its maiden flight took place two months later than intended.

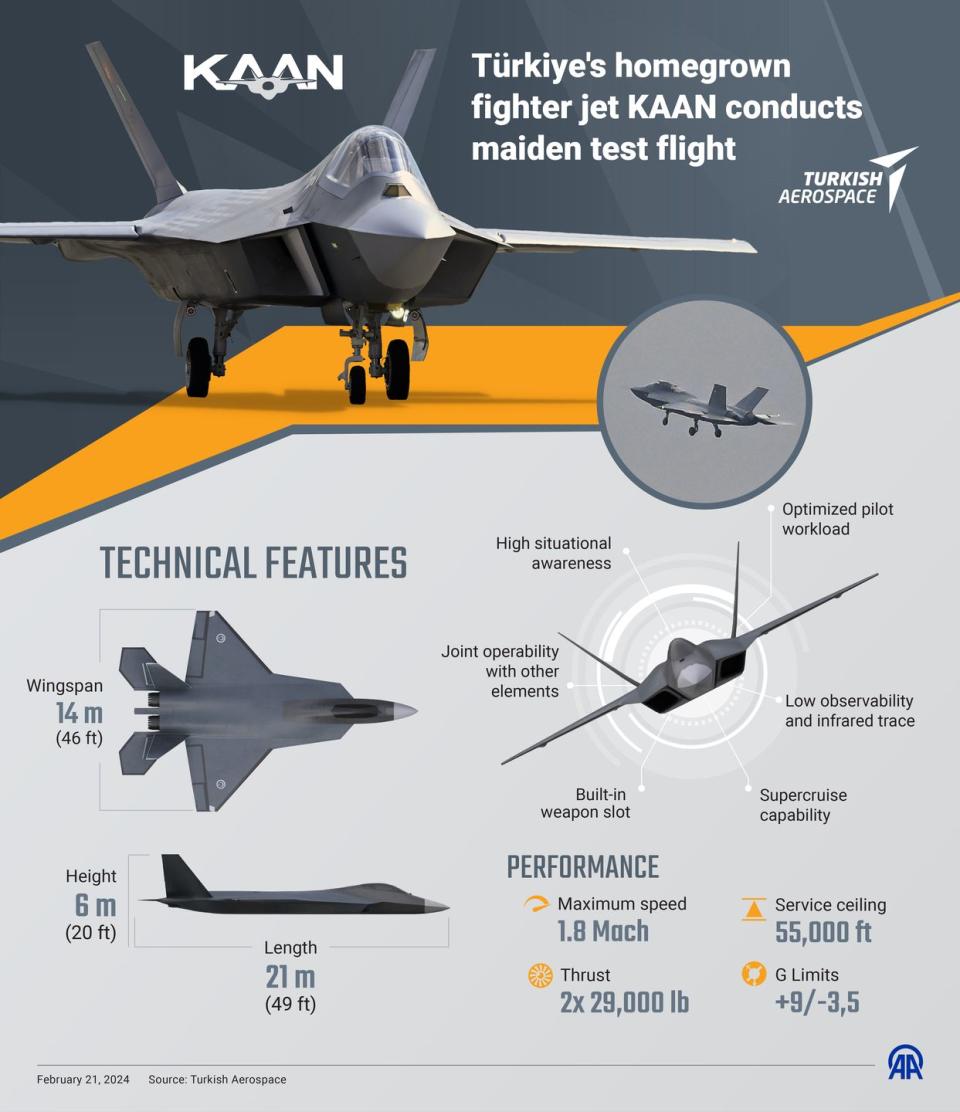

Kaan has a profile broadly similar to the U.S. F-22A Raptor stealth fighter. Sporting an aluminum nose and titanium center fuselage, its surfaces are coated with lightweight, low radar-reflective composite carbon thermoplastics that Turkish companies were originally building for F-35 jets.

As externally-mounted weapons degrade stealth, it has two small internal ‘cheek’ bays nested next to the engines able to carry two short-range air-to-air missiles each. However, configuration of the main under-fuselage bay with capacity for up to four longer-range air-to-air missiles or air-to-ground weapons reportedly took longer to finalize—though a circulating picture suggests that may have been resolved.

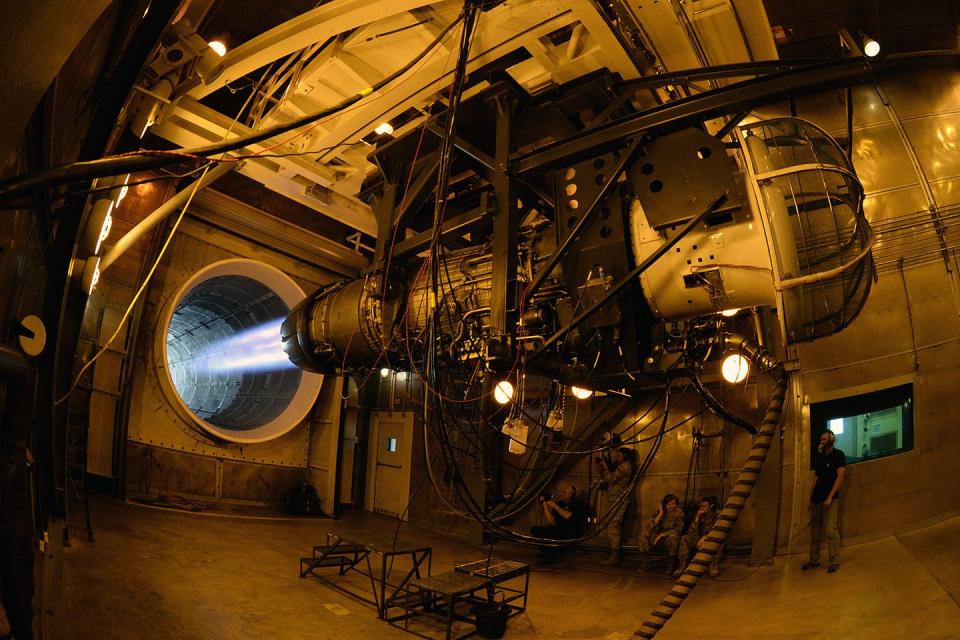

More problematically, the prototype’s American F110-GE-129 turbofan engines (also used on F-16 fighters) aren’t optimized for stealth.

The more a jet’s radar cross-section (RCS) has been reduced by its geometry and use of radar absorbent materials, the closer it can safely approach enemy fighters and air defenses and slip past or attack them before they can react. And the extent to which RCS reductions apply to the fighter’s side and rear aspect (not just the front) dictates how deep it can penetrate enemy airspace.

In respects to kinematics, Kaan is aimed to fall within typical modern fighter performance benchmarks: a maximum speed of Mach 1.8 to 2.2, service ceiling of 55,000 ft., tolerance for maneuvers exerting up to 9 Gs, and a range of 700 miles on internal fuel. It’s also expected to be supercruise-capable, i.e. able to fly sustainably at supersonic speeds without resorting to fuel-gulping afterburners. Use of two engines will raise costs but, should reduces losses to engine failures.

Kaan is to be armed with reconnaissance pods and standoff-range precision-guided weapons—including NATO-standard missiles like Meteor, and indigenous Turkish armaments like the short-range Bozdogan and medium-range Gokdogan air-to-air missiles, SOM cruise missiles (171-mile range), and MAM-T anti-tank missiles.

Avionics will supposedly include a modern glass cockpit—with voice-command AI-autopilot that can land the plane should the pilot fall unconscious—and a British Martin-Baker ejection seat (possibly the US-16E model). TAI also promises fused sensors (including a jam-resistant and stealthy AESA gallium-nitride radar by Turkish firm ASELSAN), a nose-mounted infrared sensor and a 360-degree coverage electro-optical targeting system under the fuselage (fittings for both of which are already visible), open-architecture mission systems, a helmet-mounted sight, and the capability to control accompanying Anka-3 combat drones.

In truth, Kaan still has a long journey ahead of it. The current prototype lacks mission systems. The following two prototypes, planned to fly in 2025 and 2026, should have most in place. After producing between 7 and 10 prototypes in total, delivery of the first ten Block 1- aircraft intended for military service is slated for 2030-2033. Only then is a decade of mass-production to commence (at a rate of 24 aircraft per year) to gradually replace Turkey’s F-16 fleet and serve on through the 2070s.

Unless Turkey can secure export orders to expand total orders and reduce unit costs, each Kaan is likely to exceed $100 million per aircraft—more than if Turkey had procured U.S. F-35 stealth jets with likely superior stealth features.

That is not to say Kaan won’t potentially be better tailored to fit certain Turkish requirements, including potentially better performance for within-visual-range air-to-air combat, and integration into Turkey’s growing ecosystem of indigenous weapons, sensors, drones, and battle management networks.

Just as South Korea plans to upgrade its comparable KF-21 Boramae fighter, Turkey also hopes to eventually use Kaan as the basis for a more full-featured stealth jet with AI-driven capabilities. Azerbaijan and Ukraine (both established clients of Turkish combat drones), as well as Pakistan, Indonesia, and the UAE are cited as potential future buyers.

But most importantly, as Turkish relations with the U.S. and Germany have frayed, Kaan now takes on the added importance of giving Turkey the option to build its own aircraft regardless of its relations with Western countries.

Why jet fighters have big implications for Turkish foreign relations

Kaan—or rather, TF-X—began development in 2010 when Turkey was well along the way to acquiring a large fleet of single-engine F-35 stealth jets. But worsening relations with the U.S. culminated in 2019 with Turkey’s rejection from the F-35 program, and denial of upgrades and new orders for Turkey’s large fleet of F-16 fighters.

That, in turn, forced Kaan to evolve from an air-superiority-focused fighter into a more squarely multi-role aircraft. Turkey’s comparatively mature drone industry has also seen future combat drones assume a role in teaming up with manned Kaan jet fighters—notably, the transonic jet fighter-like Kizilelma (“Red Apple”) and the more traditional Anka-3 combat drone, both jet-powered.

Kaan’s importance stems from Turkey’s shifting and often conflictual relationships with its fellow NATO states, Russia, Ukraine, and other states in the Middle East and Asia.

For example, Turkey, operates Type 214 diesel-electric submarines, F-16 and F-4 jet fighters, and Patton and Leopard 2A4 main battle tanks from the Germany and the U.S. But in the 2010s, these countries cut Turkey off from F-35s, Eurofighter jets, and German tank engines due to Turkey’s acquisition of Russian air defense missiles, human rights concerns, and conflicting Middle East agendas.

Turkey’s ejection from the F-35 program in 2019 sank Turkey’s hopes to deploy the F-35B jump jet model onto the under-construction carrier Anadolu (now a drone carrier), and opened a modernization gap for the Turkish Air Force in the 2020s by delaying retirement of Turkey’s upgraded (but aging) third-generation F-4E Terminator 2020 strike fighters.

Finally, in 2023, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan parlayed a tacit trade of the Turkish acceptance of Sweden joining NATO into U.S. sales of F-16s and F-16 upgrades that had long been refused. He also still hopes to secure a deal for 40 4.5-generation Eurofighter 2000 jets, which would require Germany to lift its block.

U.S. officials recently reiterated their willingness to sell Turkey F-35s should it retire its Russian-built S-400 air defenses. That’s arguably a favorable tradeoff—the S-400 has had some successes in over Ukrainian aerospace, but has been out-shined by the supposedly shorter-range U.S. Patriot system delivered to Ukraine. However, Erdogan has reiterated his view that this is politically unacceptable.

The sting is worsened now that Turkey’s arch-rival Greece (also a member of the NATO alliance) was approved to acquire F-35s by the U.S. and additional Rafale fighters from France (which opposes Turkish policies in Libya and the Mediterranean). Longstanding disputes over Mediterranean islands lead Greek and Turkish jets to frequently confront each other, with both states perpetually planning for possible war.

More broadly, Erdogan’s authoritarian tendencies—particularly since the failed 2016 coup—have reduced enthusiasm in Western states. However, Turkey’s control of the Bosporus strait connecting the Mediterranean to the Black Sea has long made it hard for NATO allies to fully alienate Erdogan, despite frequent conflicts of interest. And Turkey’s ability to deny passage to warships has become even more critical now that the Black Sea has become a contested warzone between Russia and Ukraine.

Helpfully for NATO, Erdogan’s late-2010s flirtations with Russia have been partially offset by growing defense-industrial partnerships with Ukraine in drones, artillery, and small warships. But relations remain tense in many places.

Turkey decisively backed Azerbaijan in its wars with Armenia—a nominally Russia-allied state increasingly turning to India and France as security partners. Turkish forces in Syria undermine the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad (backed by Russia and opposed by the U.S.) but also battle Kurdish factions (backed by the U.S.)—circumstances which lead to the downing of a Turkish combat drone by a U.S. fighter in 2023.

Turkish defense partnerships with the UK and South Korea appear healthy, however.

Kaan’s production prospects

Turkey’s complex foreign relations make its desire for independent aircraft capacity much more urgent than they might be if the country had more stable relationship with its allies.

However, while Turkey insists Kaan will use 80-85% indigenous components, the key stumbling block remains dependency on U.S.-built F110 engines, which are assembled but not produced locally by Tusas Engine Industries (TEI). For now, it’s not guaranteed that the U.S. will grant Turkey’s request to license-build F110 engines for Kaan beyond the 10 procured.

High-performance turbofans are infamously hard to perfect, with China—a country with considerable resources to throw at the problem—still working to fully ween itself from dependency on Russian engines.

To eventually replace the F110, Turkey is weighing competing proposals for a 35,000-lb thrust engine: one involving Turkish company Kale and the UK’s Rolls Royce, and the other involvng TEI and Ukrainian company Ivchenko Progress. Turkish officials have said that a third engine option is scoped as well—perhaps referring to a non-NATO state like China, Russia, or Ukraine. Turkey is also developing fully indigenous turbofan designs (TF6000 and TF10000), but these seem to fall short of Kaan’s thrust requirements for now.

Besides that, Turkish industry does benefit from relatively mature and combat-tested munitions, networks, drones, and sensors that it can adapt for Kaan. However, the U.S. aerospace sector’s notorious difficulties in finalizing development of the F-35 point to how the integration of systems often proves more difficult than expected—particularly when trying to conform to weight limits and stealth-aircraft-specific geometry and volume constraints.

Because of Turkey’s demonstrated vulnerability to being denied U.S. military exports, Kaan seems likely to complete development. The big challenge remains securing engines and avoiding delays and cost overruns (given Turkey’s ongoing inflation crisis and tumultuous foreign relations) so that Kaan remains viable by the time it enters service.

For comparison, India’s program to develop an indigenous fighter resulted in the Tejas Mk1, which (by the time it completed development) fell short of foreign alternatives, resulting in only limited procurement. But India hopes that its investment in Tejas laid the groundwork for improved Tejas Mark 1A and Mark 2 jets—and, eventually, an AMCA stealth fighter—that could give it greater aerospace independence.

Turkey surely hopes that Kaan will debut higher up the capability spectrum than Tejas did, thereby justifying a larger initial production run. Even if not as stealthy as an F-35A, a fully developed Kaan could eventually be used as the basis for a more advanced sixth-generation stealth aircraft and AI technology (something Turkey recently began researching), leading to a sustainable and viable Turkish jet fighter production capability.

Admittedly, the exact role and longevity of manned jet fighters in the 21st century remains in flux, though Turkish industry already has a strong start in building the cheaper combat drones emerging as an alternative.

You Might Also Like