As everyone exhales after last week’s bellwether sales in New York, three things are clear about the art market:

1. Timing is everything.

2. Basically, it’s a crapshoot.

3. Proceed accordingly.

But you, my savvy reader, already knew this. And yet, every season, we all are astonished by the successful flips and dramatic flops. Who were the winners and losers this time?

Big Picture

The total haul for the week by Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips was $1.4 billion, down 22 percent from last May’s $1.8 billion.

Christie’s inched out the competition with $640 million in sales, but also saw the steepest decline year on year: 30.3 percent.

Sotheby’s followed closely with $633 million in sales, down 20.7 percent compared to last May.

Phillips had the smallest tally, as usual, with $110 million, but it was the only house to see an increase from a year ago, albeit of just 1.9 percent.

Allow me to unpack a few moments from these sales to see what they tell us about the art market right now. This week, I am focusing on Sotheby’s, with Christie’s and Phillips to follow next week.

Leonora Carrington, Les Distractions de Dagobert (1945). Courtesy Sotheby’s.

Big Winner

The brightest star of the season was the Surrealist painting by Leonora Carrington that fetched $28.5 million at Sotheby’s on May 15. Now the Art Detective can reveal the name of its anonymous seller and one of the season’s big winners: Ronald Cordover, an American financier, scientist, and art patron.

The dazzling 1945 tempera, Les Distractions de Dagobert, carried an aggressive estimate of $12 million to $18 million. Carrington’s previous auction high was $3.3 million, set just two years ago.

The new price propelled the British-born Surrealist into the highest echelon of female artists, whose prices typically trail those of their male peers; although, in this case, Carrington is now ahead of popular figures like Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst.

The price represented a huge win for Cordover, who bought the painting at auction for $475,500 in 1995, outbidding the Argentinian developer and businessman Eduardo F. Costantini. (Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $990,000 today.)

That’s a 3,166-percent increase. Wow!

Costantini, the founder of the Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires, returned to the auction room last week, determined to get the painting this time around.

“This is a superb piece in the history of Surrealism,” Costantini told me after outbidding rivals from China and Miami. “I was the underbidder 30 years ago for this picture, and I didn’t want to miss it this time.” What a flex!

Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park #126 (1984).

Big Loser

Tremendous results like Cordover’s obscure the sobering reality of the art market: It’s highly illiquid. It’s hard to break even, let alone have a windfall. Yes, it happens with some regularity, but more frequently it’s a crapshoot.

Paying a record price for a work and trying to resell it soon after may not work out. One cautionary tale involves Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park #126 (1984).

I have previously identified the seller as billionaire Lorenzo Fertitta, a savvy market player who also consigned a monumental 1984 collaboration between Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

In 2018, when Ocean Park #126 came up for sale at Christie’s as part of the collection of David and Barbara Zucker, it fetched a record $23.9 million. Since then, collectors have seen it at the Lévy Gorvy gallery (now Lévy Gorvy Dayan) in Palm Beach. On May 13, it returned to the auction block with an estimate of $18 million to $25 million at Sotheby’s contemporary evening sale. There was no guarantee and no irrevocable bid.

There was also no interest in the room, on the phones, or online. After several exasperating minutes of chandelier bidding, the auctioneer dropped his gavel at $14.8 million, announcing that the lot passed.

Installation view of Untitled (1984) by Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat at Sotheby’s in May 2024. Photo by Katya Kazakina

A few lots earlier, the untitled Warhol-Basquiat collaboration brought $19.4 million against a presale estimate of $15 million to $20 million. Fertitta acquired the piece for $2.6 million at Sotheby’s in 2010, according to the provenance, which does not identify him by name.

That means that Fertitta made a killing on one painting and had to take back the other. What accounts for the strikingly different outcomes? Time and timing.

The Warhol-Basquiat last sold at auction 14 years ago. Since then, the Basquiat market has soared. And last year, the collaboration between the two artists was the subject of a major exhibition at the Brant Foundation in New York and the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. The market for these once-derided works has improved, and the final price reflected that.

The Diebenkorn, on the other hand, returned to the market just six years after its record sale at Christie’s. That was “probably a little too soon,” said Grégoire Billault, Sotheby’s chairman of contemporary art, adding that the estimate acknowledged that. (Note that the seller was prepared to take a loss if the work hammered at its low estimate of $18 million.)

Prior to the sale, Sotheby’s received offers of $16 million and $17 million, but the seller didn’t want to accept irrevocable bids or sell for less than $18 million. “This is one of the best ‘Ocean Park’ paintings we’ve seen,” said Billault. “The condition was amazing. I completely understand he decided to keep it.”

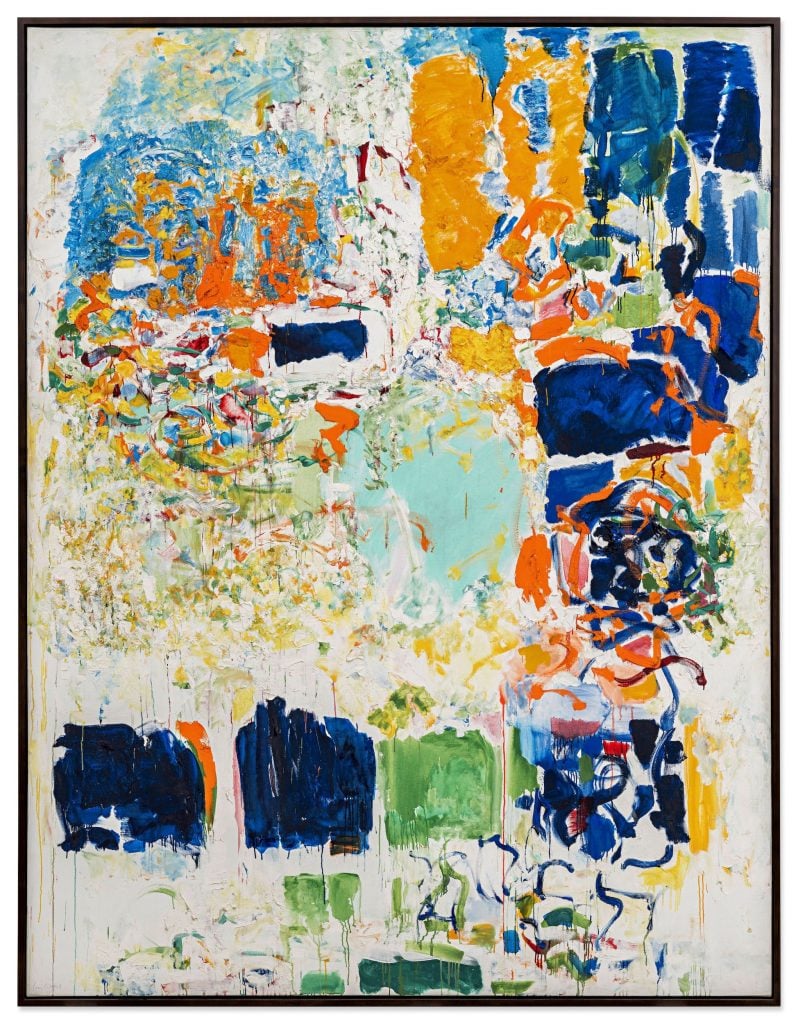

Joan Mitchell, Noon (1969). Image via Sotheby’s.

Big Seller

Greg Renker, a cofounder of Guthy-Renker, a direct-marketing company of beauty and health products, was another major consignor last week. The Art Detective has identified him as the seller of the four paintings by Joan Mitchell from four different decades, three of which ended up exceeding their low estimates.

These four works, acquired with the help of art advisor Barbara Guggenheim, were part of a bigger consignment brought to Sotheby’s by Amy Cappellazzo, I can reveal. All were designated as “property from an esteemed private collection” and carried a combined low estimate of $47.8 million. They hammered for a total of $52.6 million ($60.9 million with fees).

In addition to the Mitchell, the other lots with the same designation were Édouard Manet’s Vase de Fleurs, Roses et Lilas (1882), Pierre-August Renoir’s Portrait d’Edmond Maitre (1871), and two Wayne Thiebaud paintings, Suckers (1970) and Watermelon & Knife (1989).

The Manet is of particular note. Renker bought it in 2004, according to the Sotheby’s provenance listing, which does not mention him by name. There weren’t any comparable Manet still lifes at auction that year, according to Artnet Price Database. So, I checked with David Nash, a formidable Impressionist and Modern art dealer who procured the top masterpieces for Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen. Turns out, Nash privately sold a similar late still life by Manet in 2002 for $4.5 million. In 2018, another 1882 painting, Lilas et Roses, from the collection of David and Peggy Rockefeller, fetched $12.9 million.

Édouard Manet, Vase de Fleurs, Roses et Lilas (1882). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

In November, Renker’s Manet was on view at Christie’s with other artworks consigned for private sales, according to dealers. The asking price then was “aspirational”—about $20 million, several people in the industry told me.

It appears that Renker adjusted his expectations. Sotheby’s estimated the Manet at $7 million to $10 million. That was wise. Four bidders went after this gem of a painting, which hammered at $8.5 million ($10.1 million with fees).

Curiously, two Mitchells also hammered at $8.5 million. Go figure!

The Art Detective will bring you more auction tales next week. Stay tuned.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: