When the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jennifer Egan was in the Netherlands a few years ago promoting her most recent novel, “The Candy House,” she noticed something unexpected. Most of the people who asked her to sign books at author events were not presenting her with copies in Dutch.

“The majority of the books I was selling were in English,” Egan said.

Her impression was right. In the Netherlands, according to her Dutch publisher, De Arbeiderspers, roughly 65 percent of sales for “The Candy House” were in English.

“There was even a sense of a slight apology when people were asking me to sign the Dutch version,” Egan said. “And I was like, ‘No! This is what I’m here to do.’”

As English fluency has increased in Europe, more readers have started buying American and British books in the original language, forgoing the translated versions that are published locally. This is especially true in Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands and, increasingly, Germany, which is one of the largest book markets in the world.

Publishers in those countries, as well as agents in the United States and Britain, worry this could undercut the market for translated books, which will mean less money for authors and fewer opportunities for them to publish abroad.

“There is this critical mass,” said Tom Kraushaar, publisher at Klett-Cotta in Germany. “You see in the Netherlands: Now there is a tipping point where things could really collapse.”

The English-language books that are selling abroad are generally cheap paperbacks, printed by American and British publishers as export editions. Those versions are much less expensive than hardcovers available in the United States, for example, and much less expensive than the same books in translation, which have to observe minimum pricing in countries like Germany.

“People should read in whatever language they want,” said Elik Lettinga, publisher of De Arbeiderspers in the Netherlands. But the export editions, she continued, “undercuts on price.”

English sales have accelerated in recent years, in part because books now go viral on social media, especially TikTok. Booksellers in the Netherlands said that many young people prefer to buy books in English with their original covers, even if Dutch is their first language, because those are the books they see and want to post about on BookTok.

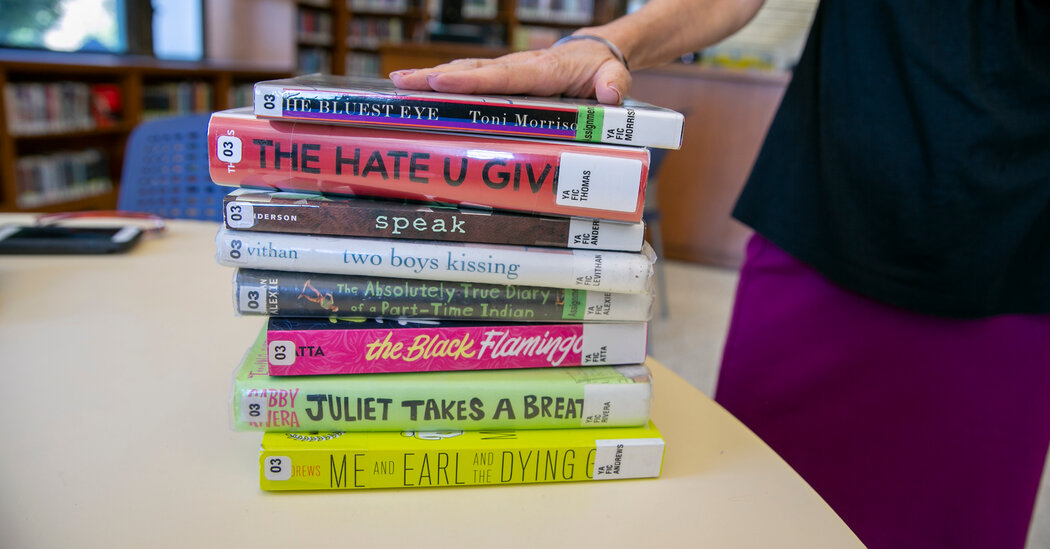

In some bookstores in Amsterdam, young adult sections carry mostly English-language books, with only a handful of Dutch options.

Leon Verschoor, a bookseller at Martyrium, a store in Amsterdam, said he had seen a real shift over his 30-year career in the book business. Those young readers, Mr. Veerman said, “they’ll never read in Dutch.”

As the English versions cut into sales of translated titles abroad, it becomes more difficult — and sometimes impossible — for European publishers to recoup their costs when they publish a work from the United States or Britain. While major blockbusters will continue to be translated, publishers say, books by midlist authors may not be.

Christian Schumacher-Gebler, chief executive of the Bonnier Publishing Group in Germany, said this could hit authors in many ways. They would miss out on royalties from translated editions, which are higher than the payment they receive from inexpensive export copies. Also, the English-language books sent to Europe might not sell as well without a local company to run the ground game.

“An English publisher simply doesn’t have a P.R. strategy in France or Germany or the Netherlands,” Schumacher-Gebler said.

In an effort to combat the English-language appeal of TikTok, some Dutch publishers have started to release translated books under their English titles, with covers that are similar, or the same, as the original designs. The Dutch version of R.F. Kuang’s 2023 novel “Yellowface” looks identical to the original, including the English title.

“We are in the middle of a transition,” said Simon Dikker Hupkes, a commissioning editor at the Dutch publisher Atlas Contact. The fact that many readers overlook the Dutch translations, he said, “hurts our hearts a little.”

Asha Hodge, 19, who described herself as an avid reader, said she preferred to read in English because she enjoyed posting about books in English on her Instagram account.

Ms. Hodge is part of a 35-person group chat named “Dutch Booksta Girlies,” which consists of women who befriended each other on Instagram while discussing books. The other Dutch people in the group agreed that they preferred to read in English, said Ms. Hodge, who lives in the eastern city of Enschede.

Bookstores have adapted to the trend, buying more English-language versions of popular books or focusing on English editions of young adult novels.

“We neglect our language,” said Peter Hoomans, a seller at Scheltema, a bookstore in Amsterdam.

Some booksellers in the Netherlands said that they were pleased that people were buying books, regardless of the language. Jan Peter Prenger, the chief buyer at Libris, a large group of independent bookstores in that country, said he welcomed the trend of reading in English and the large number of new, young readers it brings.

For the first time since the 1960s, he said, 15-year-olds are back in bookstores in droves. “That’s gold,” he said.