WASHINGTON — The controversy over Native American names in professional and collegiate sports arrived at the White House on Monday, when President Biden hosted the Atlanta Braves, winners of last year’s World Series.

The team’s name and its accompanying tomahawk logo have long come under criticism as offensive to Native Americans. During games, Braves fans mimic a “tomahawk chop” while crudely simulating Native American battle chants. That practice has also received scrutiny, most recently when the Braves defeated the Houston Astros in six games last year to become Major League Baseball champions.

“We have repeatedly and unequivocally made our position clear — Native people are not mascots, and degrading rituals like the tomahawk chop that dehumanize and harm us have no place in American society,” Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians, said last year.

A reluctant culture warrior, Biden made no mention of the controversy over the name during the White House ceremony, which has become a traditional event for professional and collegiate sports teams.

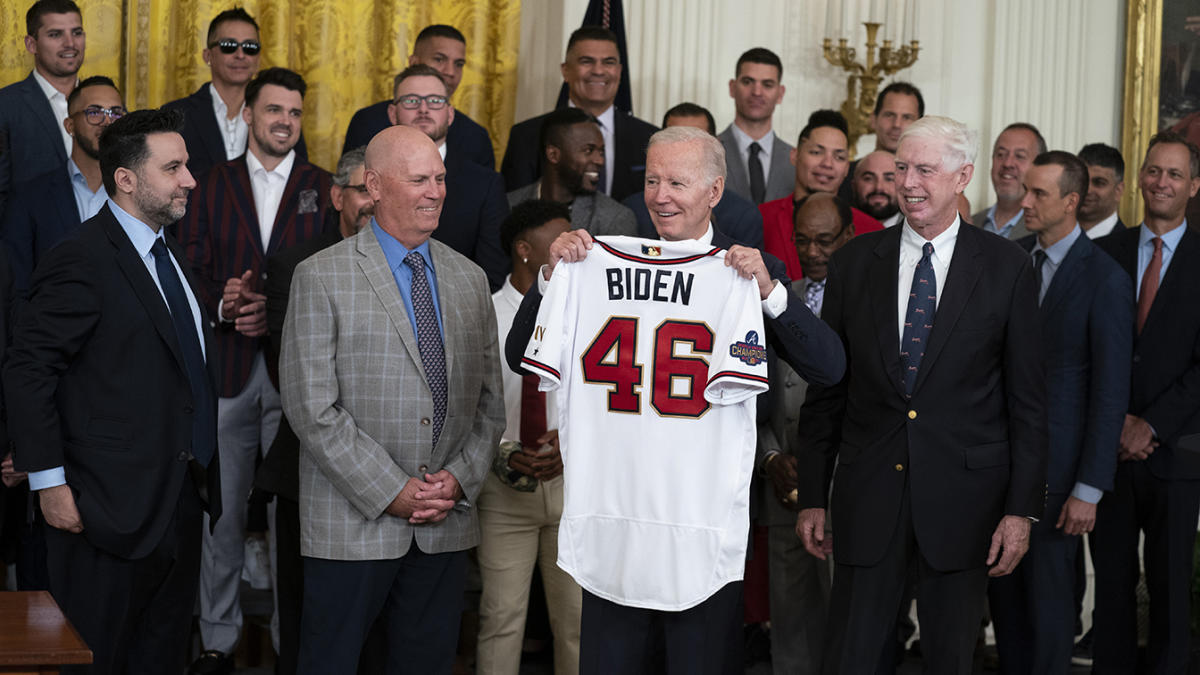

“Atlanta is a great American sports city,” Biden said as he was presented with a Braves jersey bearing the number 46 (he is the 46th president). “And the Braves are a big reason for that. This team has literally been part of American history for over 150 years.”

Later in the day, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre was asked by a reporter about the debate over the Braves’ name and the tomahawk chop. The team has said it would not consider a name change, but other organizations have made similar avowals, only to eventually relent in the face of public pressure.

“We believe it’s important to have this conversation. Native American and Indigenous voices, they should be at the center of the conversation,” Jean-Pierre said.

“That is something the president believes,” she continued. “That is something this administration believes. And he has consistently emphasized that all people deserve to be treated with dignity and respect. You hear that often from this president. The same is true here. And we should listen to Native American and Indigenous people who are most impacted by this.”

The Republican Party promptly shared a video clip of Jean-Pierre’s response on Twitter, in evident hopes of arousing sentiment against Democrats in Georgia, which is hosting crucial races for governor and the U.S. Senate this year.

Jean-Pierre did not respond to a Yahoo News request for elaboration.

Some conservatives see the removal of Native American names as empty gestures and an attack on the athletic logos they’ve come to adore over the decades. But during a period of intense racial reckoning, it has become harder to justify symbols of a legacy that is, according to many historians and activists, rife with murder and exploitation.

In the summer of 2020, the Washington Redskins of the National Football League became the “Washington Football Team” while deciding on a new name (eventually settling on the Commanders). The Cleveland Indians — whose logo was a cartoonish rendition of a Native American — became the Guardians. The changes bothered then-President Donald Trump, who lamented on Twitter that the teams were “changing their names in order to be politically correct.”

Because Trump was such a polarizing figure, some championship sports teams stayed away from the White House during his time in office. But during the Obama administration, the Chicago Blackhawks of the National Hockey League visited the White House on three occasions, delighting the president, a Chicagoan, with their Stanley Cup victories.

Although the Florida State Seminoles won the collegiate football championship in 2013, a White House visit never materialized, in what some perceived as an intentional slight. That same year, Obama called on the Redskins to choose a new name. “If I were the owner of the team and I knew that the name of my team … was offending a sizable group of people, I’d think about changing it,” he said.