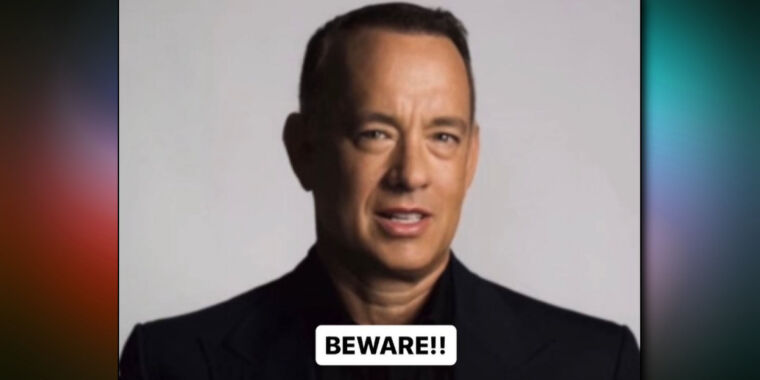

Tom Hanks

News of AI deepfakes spread quickly when you’re Tom Hanks. On Sunday, the actor posted a warning on Instagram about an unauthorized AI-generated version of himself being used to sell a dental plan. Hanks’ warning spread in the media, including The New York Times. The next day, CBS anchor Gayle King warned of a similar scheme using her likeness to sell a weight-loss product. The now widely reported incidents have raised new concerns about the use of AI in digital media.

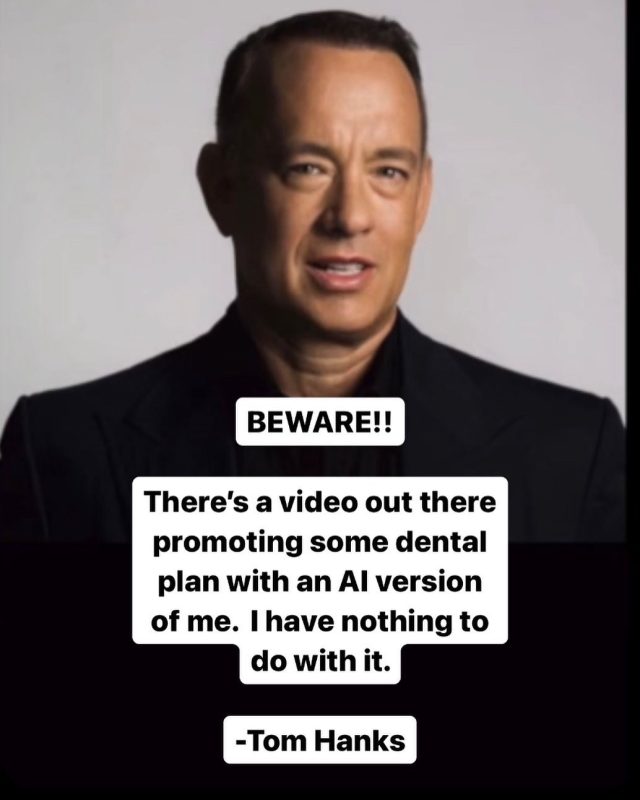

“BEWARE!! There’s a video out there promoting some dental plan with an AI version of me. I have nothing to do with it,” wrote Hanks on his Instagram feed. Similarly, King shared an AI-augmented video with the words “Fake Video” stamped across it, stating, “I’ve never heard of this product or used it! Please don’t be fooled by these AI videos.”

Also on Monday, YouTube celebrity MrBeast posted on social media network X about a similar scam that features a modified video of him with manipulated speech and lip movements promoting a fraudulent iPhone 15 giveaway. “Lots of people are getting this deepfake scam ad of me,” he wrote. “Are social media platforms ready to handle the rise of AI deepfakes? This is a serious problem.”

Tom Hanks / Instagram

We have not seen the original Hanks video, but from examples provided by King and MrBeast, it appears the scammers likely took existing videos of the celebrities and used software to change lip movements to match AI-generated voice clones of them that had been trained on vocal samples pulled from publicly available work.

The news comes amid a larger debate on the ethical and legal implications of AI in the media and entertainment industry. The recent Writers Guild of America strike featured concerns about AI as a significant point of contention. SAG-AFTRA, the union representing Hollywood actors, has expressed worries that AI could be used to create digital replicas of actors without proper compensation or approval. And recently, Robin Williams’ daughter, Zelda Williams, made the news when she complained about people cloning her late father’s voice without permission.

As we’ve warned, convincing AI deepfakes are an increasingly pressing issue that may undermine shared trust and threaten the reliability of communications technologies by casting doubt on someone’s identity. Dealing with it is a tricky problem. Currently, companies like Google and OpenAI have plans to watermark AI-generated content and add metadata to track provenance. But historically, those watermarks have been easily defeated, and open source AI tools that do not add watermarks are available.

A screenshot of Gayle King’s Instagram post warning of an AI-modified video of the CBS anchor.

Gayle King / Instagram

Similarly, attempts at restricting AI software through regulation may remove generative AI tools from legitimate researchers while keeping them in the hands of those who may use them for fraud. Meanwhile, social media networks will likely need to step up moderation efforts, reacting quickly when suspicious content is flagged by users.

As we wrote last December in a feature on the spread of easy-to-make deepfakes, “The provenance of each photo we see will become that much more important; much like today, we will need to completely trust who is sharing the photos to believe any of them. But during a transition period before everyone is aware of this technology, synthesized fakes might cause a measure of chaos.”

Almost a year later, with technology advancing rapidly, a small taste of that chaos is arguably descending upon us, and our advice could just as easily be applied to video and photos. Whether attempts at regulation currently underway in many countries will have any effect is an open question.