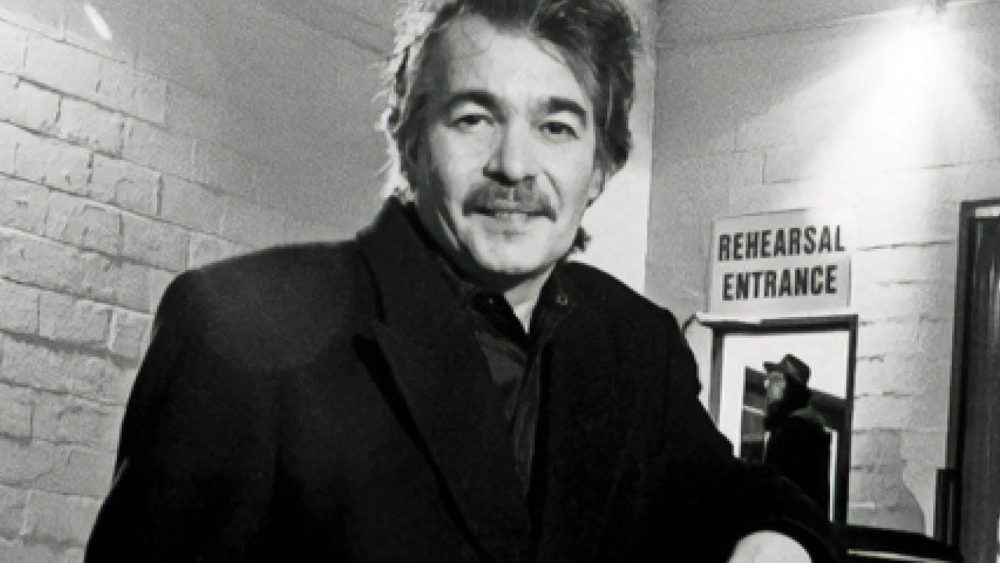

For the millions who loved him, John Prine was an angel from Illinois. The singer-songwriter had a 50-year career trajectory that went the full distance from being part of the “next Dylan” brigade in the early ’70s to inspiring Next-John-Prines by the thousands before his death in April 2020. He would have turned 77 on Oct. 10, and the phrase “would have” isn’t just a figure of speech here; for all his health issues over the years, his being cut down by COVID at the beginning of that epidemic felt like seeing an oak unfairly felled in its prime. But “John Prine” as a lingering presence, as a brand and as an aspiration isn’t going to slip away in the culture any year soon.

There’s a fresh way to revisit Prine apart from the catalog of records he left behind. Five decades’ worth of stories about and conversations with the artist have been collected by Holly Gleason in “Prine on Prine: Interviews and Encounters With John Prine,” newly out as a 360-page trade paperback from Chicago Review Press. Gleason grew up on him before she became a close observer as a bicoastal music journalist and confidante as a Tennessee friend (and, in passing at a key point, his publicist). Digging through materials that sometimes never made it online, she’s included seminal Prine encounters with Cameron Crowe, Studs Terkel and the Los Angeles Times’ Robert Hilburn, on up through some of the wealth of press he attracted in his last years (including a short Variety piece about an abortion-rights charity single) and the final extensive interview he ever gave.

To know him is to love him, and to love and know Prine is to spend a lot of hours in his presence via Gleason’s essential compendium, which finds his observational candor, fierce intelligence and genial warmth to be unwavering over a half-century of meeting the press. On the eve of Prine’s birthday, we talked with Gleason (who has been a Variety contributor herself) about what struck her in assembling the book.

We see “collected interviews” books once in a while with musicians or filmmakers who’ve met the press, as it were, over periods of decades. Aside from having just been at the game for 50 yeas by the time he died, why was Prine a prime candidate for this?

Because across the six decades that he wrote songs, he nailed not just the human condition, but saw the vulnerable, overlooked and thrown-away in an honest way that never removed their dignity. Plus, he was hilarious and kind and funny. So much more than the Americana saint he was seen as at the end.

And for people to understand the hayseed kinda kid from outside Chicago, who was in the Army, delivered mail who became the first “new Dylan” – and how he navigated a business based on a jacked-up kind of momentum? It’s a gift to see someone willing to walk away from the big music business game and create a wholly functioning record label almost out of nothing with Oh Boy Records, then stay true to it. Plus the context of who he was in each of these moments, it’s a fascinating social history of an artist and a lot of social movements and attitudes.

Can you sense anything changing for him over the 50 years, in the way he conducts the interviews – softening or toughening up, getting more wary or more open, changing the kind of language he uses in talking with journalists?

Two things struck me putting this together. First, his honesty and truth never wavered… It’s why there’s some repetition, but his story never shifts, is never exploited for the moment – or to create some “sense” of who the media might’ve wanted him to be.

Second, over time, he got more comfortable with the fame part. He was always just John, someone who thought the hoopla was goofy and had really high standards of writing. But the idea of “being John Prine” became something easier, then turned into something that allowed him to make other people happy. He loved that.

Did he want to make people laugh in conversation, the way he often did in song?

John loved to make people laugh, and he was funny without cracking jokes. But mostly in conversation, I think, he was very true to the nature of the question. Although if it got too serious, he’d find a way to make you laugh to make a point.

What is your favorite interview that you included in the book?

I’m a little prejudiced: Ronni Lundy’s contributions from her brilliant Southern heritage cookbook “Shuck Beans, Stack Cake & Honest Fried Chicken,” because it contains the world’s greatest pork roast recipe. I used to beg John for the recipe; he’d just grin, saying, “Nope! You want a pork roast, you call me and I’ll make it.”

I’m also partial to John Mellencamp’s speech from the PEN Awards presentation. Beyond how personal it was, it really provides a sense of how much some of the biggest rock and pop forces of the last half century loved him.

Did journalists see him as a “next Bob Dylan” in those earliest years, the way singer-songwriters of the ‘70s were sometimes tagged?

John was the original “next Bob Dylan.” His self-titled first album came out in 1971 when Dylan was laying low, so people were looking for someone digging deeper into life, writing with profound metaphors and allusions — and there John was with “Sam Stone,” “Hello in There,” “6 O’Clock News,” “Donald & Lydia,” “Paradise,” “Spanish Pipedream,” “Illegal Smile,” “Angel From Montgomery”… pretty much the entire album. The dice were cast.

He used to tell a story – and it’s in one of the interviews – about Dylan coming up to him at someone’s apartment in New York when he’d been out of sight after the motorcycle wreck. Dylan walked up to John singing the words to the songs on that first album, which shocked Prine in the moment. But maybe it made living with the heaviest yoke in ‘70s/’80s singer-songwriter culture a little easier to deal with, too.

How easy or difficult was it to find good interviews to include in the book, especially early ones?

So much journalism from the pre-internet age is almost lost. The Country Song Round Up piece was located because I knew the editor, who went down in his basement and found it. Cameron Crowe had to go into his files, find that piece (from the L.A. Free Press) and scan it, then send it. Robert Hilburn had to use his library account to access his L.A. Times pieces. The folks at Meredith didn’t even know the People magazine profile existed. They asked me to send them a copy.

I was there for so much of John’s life post-“Aimless Love” — his first full Oh Boy album — so I knew where the bodies were buried, if you will. Dan Einstein, my boyfriend, then fiancée, really was the one who built that label… He helped me cull these stories and made some calls on my behalf to get permissions and make connections. [Einstein died in January 2022.] George Dassinger, who’d run Elektra’s press department in the ‘80s, repped “The Missing Years” and “Lost Dogs + Mixed Blessings.” He kept meticulous files and graciously sent me everything. And I did the press for “In Spite of Ourselves” and “Fair & Square.” I kept everything, too.

If someone was to read the interviews in chronological order, do you think we’d notice anything changing about his attitude?

I think he relaxed more and more, and became almost the caretaker to these songs and the people in them, as well as those who loved them. He didn’t like talking about himself, but loved talking to people.

And he was so grateful as time went on. That really shines in Michael McCall’s piece for the Nashville Scene. It’s in my piece for Paste. It’s in his SiriusXM Outlaw Country interview with Dave Cobb for “The Tree of Forgiveness.”

Were there “lost years” when he was no longer a hot young guy and before his rediscovery happened in a big way? If so, was he taking that in stride? It can’t have hurt that he knew music writers knew him and were on his side… well, at least the ones in the book.

Well, the writers who loved him “got” it, but you’d be shocked the number of rock critics who just didn’t care – or thought he didn’t matter because he didn’t have a major label when he started Oh Boy. Or they were chasing what was new.

There were people whose opinion he cared about, but I also know he had a creative soul that was really the compass. He’d go years without an album, happy as could be. He’d be living his life, fishing, looking for classic cars, hitting “meatloaf day” all over town, then playing shows for the people who passionately wanted to hear those songs. As long as he could go play, make enough money to pay the bills – and never betray his music – he was good.

Who in the book do you feel like kind of nailed him as far as really getting to his essence?

Most of the people who have multiple entries, which is why they’re in there. It shows how his relationships with writers deepened. Robert Hilburn initially, who was both an advocate and someone slicing into the heart of his music. His piece when John had separated from Elektra/Asylum saw John so snarky and spot-on. Dave Hoekstra, first in the Illinois Entertainer, then the Chicago Sun-Times, had that Chicago/straight-up Midwestern thing. In both cases, you can feel it in the details and the quotes.

Also, Mike Leonard’s two “Today Show” pieces. John took him way inside his world, let him film around in Nashville and on the road. The humanity and honest working man’s values just shine.

What were your experiences with him like, as a journalist? How was it sort of knowing him off-camera, as it were, as a friend or acquaintance who would come back into your life via mutual pals or loved ones? Did that affect the way you wrote about him?

[In a first attempt to interview Prine] Dan Einstein told me John didn’t talk to college papers, then hung up. Three months later, I was the Miami Herald writer assigned to preview Prine’s Carefree Theater concert in West Palm Beach. After being told he hated doing interviews, I couldn’t believe we stayed on the phone for two hours and 40 minutes — laughing, talking about records we loved, people we knew, the Midwest, starting his label where people had to send their money to a post office box.

When the story got spiked because I took a job at the Palm Beach Post, I went to apologize. He told me, “Well then, it was like friends talking…” He started working me on [the Oh Boy! release] “Tribute to Steve Goodman,” which beat his “German Afternoons” for the first contemporary folk Grammy. Stevie, who wrote “City of New Orleans” and co-wrote “You Never Even Called Me By My Name” with John, had died from leukemia, and that double-album set at Chicago’s Aerie Crown Theater was an homage to his friend and the Chicago folk scene that birthed both of them. Just as importantly, the famous version of Bonnie Raitt and John singing “Angel From Montgomery” came from that project.

John was very family-oriented, very much a solid Midwestern guy. I always figured I was the right age to be a child from his first marriage. He went out of his way to get me fixed up with his co-manager Dan Einstein; even gave Dan his credit card to take me out on our first proper date. That’s John: just so real, concerned about the people he loves.

People think of him as the primary icon of Americana, which didn’t exist for most of his career as a known genre. Some people think country, although that didn’t really seem to be his thing — although he did fit into Nashville as a greater community. Did he find a kind of spiritual home being in or adjacent to these genres even though they were late in coming or not being an exact fit?

Truth? He didn’t care. He didn’t make music to fit a slot; he made the music that was in his heart. Look at the producers he worked with – from Jerry Wexler and Arif Mardin to Knox and Jerry Phillips with their dad Sam Phillips, Howie Epstein to Jim Rooney, Dave Cobb. Some were these churlish rock records, others hootenanny folk records, bluegrass/country standards with Mac Wiseman. But they were mostly records built around the songs, well-played and supple.

If you read the Mike Leonard “Today” scripts, you get the sense he was more interested in getting it right for the people who loved the songs — he was selling out Wolf Trap in the mid-‘80s — than he worried about being important in some “format.” When Americana became a song-driven place where a lot of his peers — Bonnie, Kris Kristofferson, Iris DeMent — made sense, it was also an awesome home for him.

Though his dad listened to the Grand Ole Opry on WSM-AM every Saturday night and he loved old classic country records, John never aspired to have anything to do with the country music business. He almost sold Oh Boy to CBS Nashville in the ‘80s, then walked away from the deal.

As for rock radio, like Bonnie, Little Feat and Warren Zevon, he initially was played on AOR stations. When the genre toughened up, there wasn’t room for him. But look at who’s on “The Missing Years”: Tom Petty, Bruce Springsteen, Christina Amphlett from the Divinyls, Bonnie. He felt very comfortable in those rooms.

Does he come off as a contented guy, as most of us probably think of him in later years? Is the tortured artist thing completely absent?

He comes off as a very true guy. Whether it’s the night of two shows in the Village with Jay Saporiti from the Aquarian Weekly, shooting the breeze with Bobby Bare on his TNN show or sharing thoughts with then-U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser at the Library of Congress, he’s just so present — and yes, grateful. Sometimes a little awed, even savoring the details of talking about things he love whether it’s hot rods, pork roast or Chicago with Lloyd Sachs, who does that wonderful No Depression cover story that serves as a Prine retrospective after his cancer surgeries.

John liked nothing more than holding court with friends, laughing and cutting up. He loved being around music being played, and he had a momentum when things were fun that would just carry him to the next morning. I can see him now, sitting at the bar at Memphis’ Peabody Hotel, waiting for the ducks to march – and just enjoying everything about it. If someone wanted to talk, fine; if it was just him a few friends, good, too.

As long as you weren’t mean or a closed-minded loudmouth, John was good. Life was good. He was in his prime, playing songs that made people very happy. He loved his kids, his wife and his life, had a great band. Everything else was gravy.