Your typical 30-lot contemporary art auction can be over in an hour, but the prep-work involved for those who are participating in it lasts much longer. Late on Tuesday afternoon, art adviser Dane Jensen sat at the zinc bar of a French bistro in midtown Manhattan. Wearing stylish attire that has come to be a constant feature at an art auction, in this case, a green Gucci sneakers, matching green sweater, dark gray pants, and a navy blazer, he flipped through the catalog for Phillips’ two-part sale of 20th century and contemporary art , which was due to start a few blocks away that evening. No sooner had the clock struck five–just an hour to go before the sale started–than Jensen’s phone lit up with text messages. He answered them swiftly, then made a call to check in on a few bids.

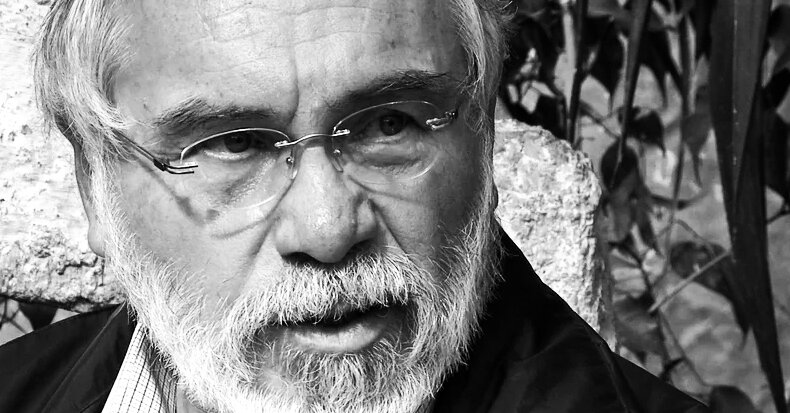

The names of art advisers aren’t typically known beyond their clients and a circle of art world insiders, but Jensen became unusually visible last year when he and another bidder went head-to-head for Ernie Barnes’s The Sugar Shack at Christie’s. Jensen didn’t win, but he helped push the price to a record-setting $13 million , around 80 times its pre-sale estimate. His enthusiasm for that Barnes’ work stemmed from his theory of collecting, honed from his years as director of contemporary art and auctioneer at Bonhams in Los Angeles and as a senior director with Gurr Johns advisory: go for lesser known, likely undervalued works by blue chip artists.

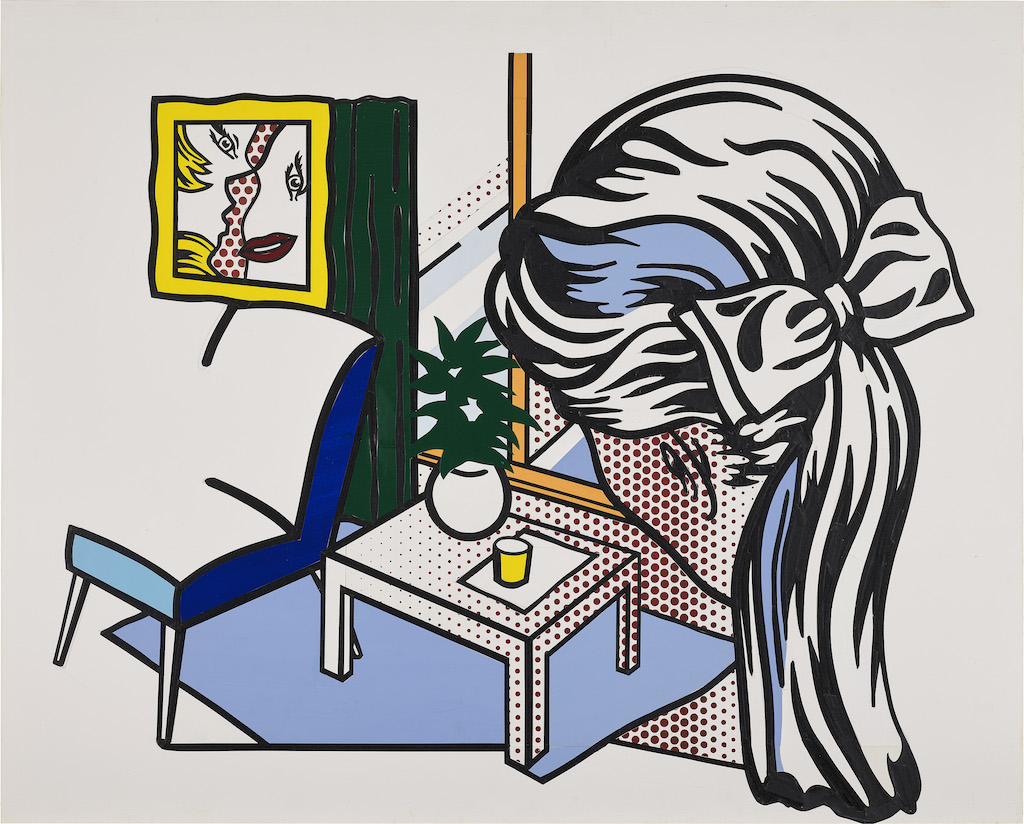

“See, this Lichtenstein is super interesting,” Jensen said, pointing to Lichtenstein’s Woman Contemplating a Yellow Cup (Study), lot number 15 in the Phillips sale. “These are the kinds of opportunities I tend to look for. A well-known market that perhaps has an overlooked segment.” The Lichtenstein, a late work made around the time of his Guggenheim retrospective, was originally categorized as a study, but has been re-christened a collage, an acknowledgment of the tape and cut paper the artist used when he made it in 1994. Paintings by Lichtenstein can run into the tens of millions; the collage was estimated to sell for between $1.5 million and $2 million.

“The market for this kind of work by Lichtenstein has already started to move,” Jensen said, “but if you have a client that isn’t ready to spend ten or thirty million on a work, but they want a Lichtenstein, this is a cool, emerging category they can comfortably jump into.”

As auction game time grew closer, Jensen’s phone continued to burble to life. “Sometimes this stuff happens really fast, you know,” he said. “My job is to put my client in a position to win. Sometimes that means talking with the specialists to gauge interest and hint at what we are looking for. Maybe mention what you’re willing to spend. But you always want to have something in the tank in case you want to get after it.” Naturally, things evolve during the heat of the auction. Jensen compared auction season to an elaborate dance. “You want everyone to be prepared, the client especially, because when it comes to bidding time, you really don’t know what will happen.”

Leaving the bar with a reporter, Jensen walked the few midtown blocks to Phillips, switching between calls and texts with the facility of a Hollywood agent. Before entering the fray, he had a few last words about the tricky business of estimates.

“If the estimates don’t match up with what something costs historically at auction, then I have to warn my client. ‘Be prepared to look for something else.’ I’ll always tell them … ‘this is the number we’ll need to be competitive, according to the data, but this is the number we’ll need if things don’t go to plan.’”

Paddle movements during an auction can be subtle. Sometimes a simple nod in the direction of the auctioneer can indicate a bid increase. Even in the room, collectors, and the advisers who they employ, often prefer anonymity. The Lichtenstein sold for a solidly-within-estimate $2 million. It really is a nice picture. And if Jensen bought it for a client, he’s not telling.