Implicit in a visit to Versailles is the slightly macabre thrill of experiencing a culture so excessively decadent that it violently upended a nation. But the former seat of the French monarchy also catalyzed another, more progressive, revolution—a scientific one.

For evidence, look no further than the Palace’s surrounding gardens. The five-mile-squared grounds were mapped out by geometricians and astronomers; keeping the 14,000 fountains bubbling further required developing an unprecedented hydraulic engineering system. The star creation was the Marly Machine, a giant thing of 40-foot paddle wheels and hundreds of pumps that could deliver a million gallons a day (it still wasn’t enough).

Versailles’s era of science was ushered in by Louis XIV’s chief minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who convinced the king to create a National Academy of Science in 1666. The Academy was eventually installed in the Louvre and over the next 120 years (with varying degrees of interest and meddling from Louis), proved a feverish incubator that brought both prestige to the crown and everyday solutions to the masses.

Jean-Dominique Cassini’s Map of the Moon, engraved by Jean Patigny, 1679. Photo: courtesy Observatoire de Paris.

This lesser-known side of 17th- and 18th-century France is the focus of “Versailles: Science and Splendour,” a forthcoming exhibition at London’s Science Museum. It’s a reprise of an exhibition hosted nearly 15 years ago at the Palace with a quixotic array of artifacts carted across the channel for the occasion, many for the first time.

“Science was at the heart of the French royal court,” said Sir Ian Blatchford, director of the Science Museum Group, “from the engineering innovations needed to build the regal seat of power to the lavish scientific demonstrations staged for the kings.”

At its inception, the Academy was an informal institution and Louis XIV, who was much more taken by art and music, simply insisted that the work should be useful. One task deemed suitable was accurately mapping the territory over which he ruled. Jean Picard took on the challenge using wooden rods and a theodolite telescope to map first Paris and then France (Newton would later cite Picard’s data in his theory of gravitation). Giovanni Domenico Cassini, who headed the Paris Observatory, turned skyward, mapping the moon with a precision that wouldn’t be matched until the late 19th century.

Optical microscope by Claude-Siméon Passemant, Jacques Caffieri and Philippe Caffieri, 1750. Photo: Château de Versailles/ Christophe Fouin.

Louis XV proved a more committed patron of the sciences and set up a research space at Versailles where resident scholars could work. Astronomy and botany were of particular interest. A space at Versailles was dedicated to showing scientific instruments of the Academy, such as microscopes and clocks showing the phases of the moon, and dolled them out as diplomatic gifts.

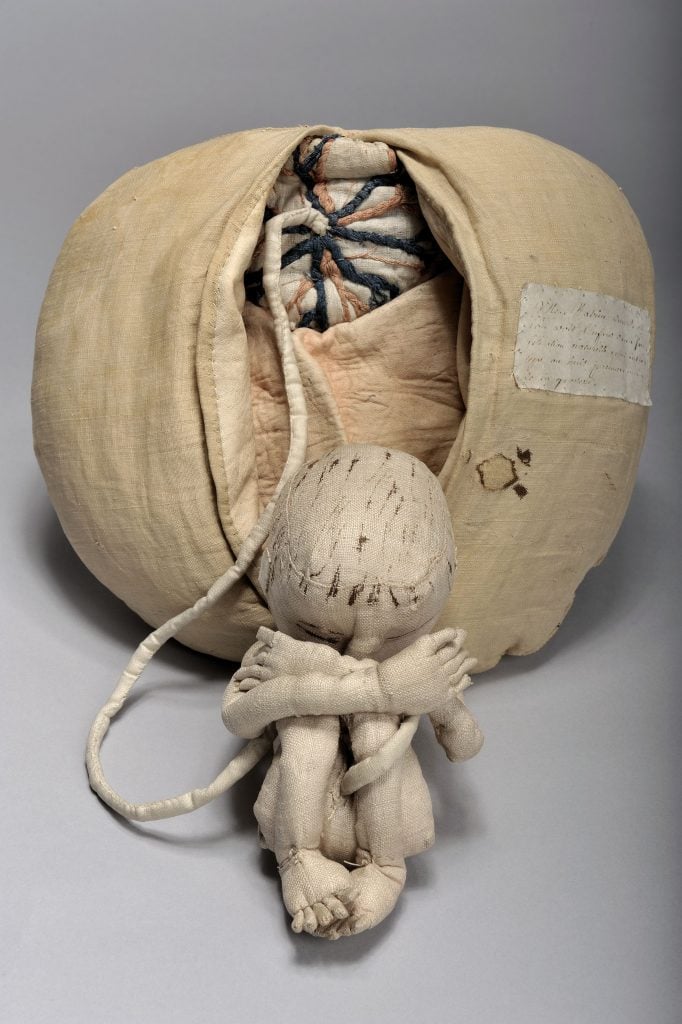

Part of the Mannequin of Madame du Coudray to teach midwifery. Photo: Musée Flaubert and the History of Medicine.

In other instances, such investment ameliorated the lives of ordinary French citizens. The story of Madame du Coudray is one such case.

Born into a family of doctors, she developed a system for teaching midwifery and published Art of Delivery, a textbook on the subject. Keen to reduce perinatal mortality in the wake of the Seven Years War, 1754 to 1763, Louis XV commissioned Madame du Coudray to travel the country and instruct peasant women and surgeons alike. She is estimated to have taught 30,000 students in the course of her career with the only surviving model of the mannequin she used exhibited.

Ascent of a Montgolfier balloon, 1783. Photo: courtesy Science Museum Group.

Even amid France’s increasingly chaotic situation, science strode on under the reign of Louis XVI. Hundreds gathered in the courtyard of Versailles to watch the flight of a hot-air balloon, agronomists developed a hardier potato capable of feeding the masses, and an inoculation against smallpox was discovered (one Louis XVI himself submitted to).

When the bloody end came in 1793, it took the Academy with it. Within two years, the revolutionaries realized they need scientists after all and resurrected an organization that continues to this day.

“Versailles: Science and Splendour” will be on view at the Science Museum, Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London, December 12, 2024–April, 21, 2025.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: