Growing up, our biggest fear was “the bomb.” Dr. Strangelove came out the year I was born. Not to worry though, see a bright flash … just duck and cover. Yep, your desk will so shield you from a thermonuclear blast. This week, I interviewed historian Niall Ferguson. He believes we’re several years into a second Cold War. Fellow geopolitical gangster Fareed Zakaria calls it a Cold Peace. Regardless, there’s definitely a cold front moving in, but you wouldn’t know it looking at America. Our minds are elsewhere, and our guard is down.

War and Innovation

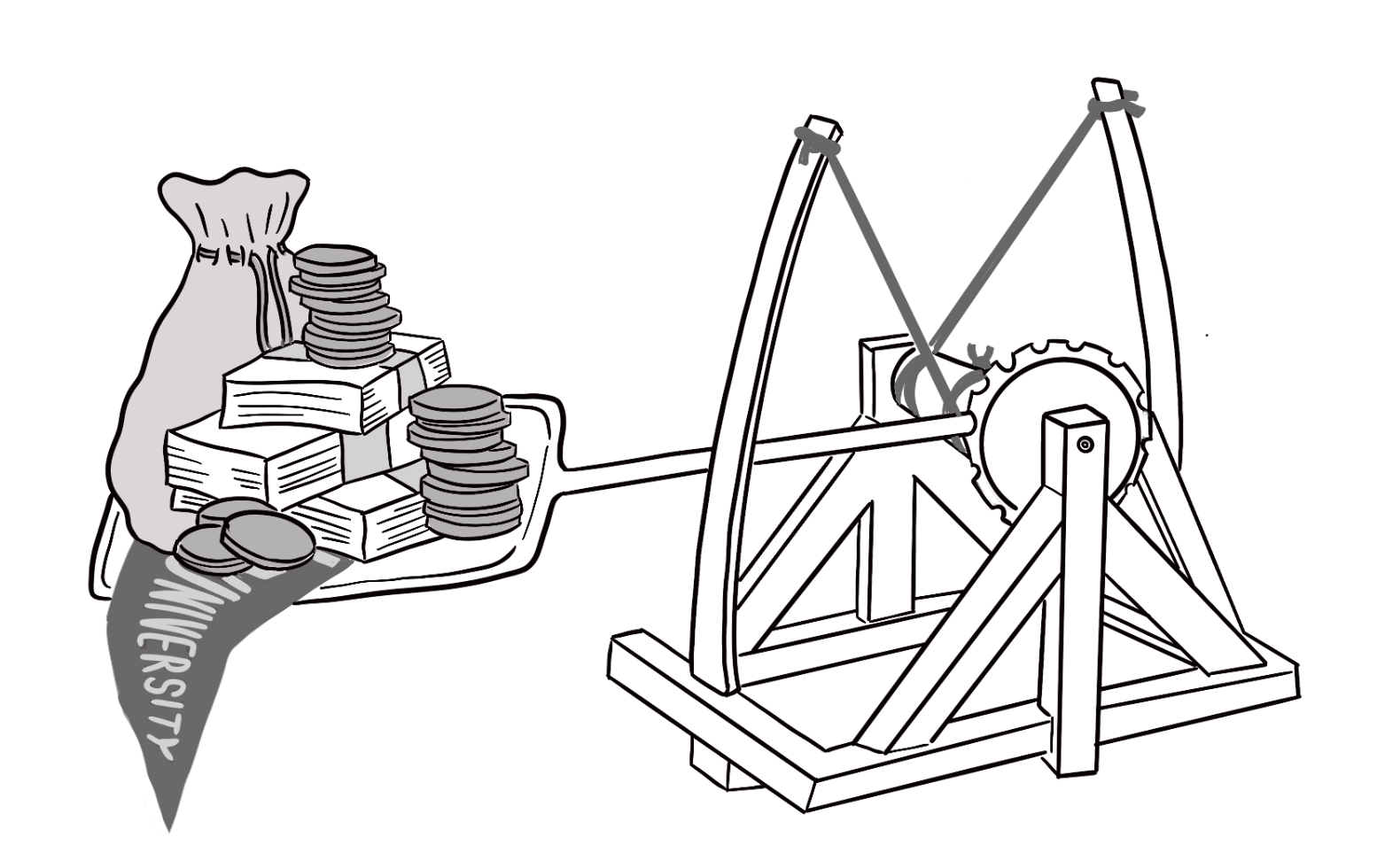

Nothing focuses one’s attention like the threat of imminent death. The first guy to use a sling to hurl a rock at his enemy was an innovator. The people who forged swords and shields from a copper-tin alloy spawned the Bronze Age. The U.S. Civil War saw the arrival of hot air balloons for aerial reconnaissance, the first organized army ambulance corp, the mass adoption of railroads, the telegraph, and photojournalism.

The dividends from World War I included stainless steel, zippers, and daylight savings (hard pass). Just one madman invading Europe in the middle of the last century brought us flu vaccines, mass adoption of penicillin, blood plasma transfusions, radar, computers, and countless other products. If it wasn’t for a Cold War-era Darpa project that laid the foundation for the commercial internet, No Mercy / No Malice would arrive via post. The 20th century was defined by the symbiotic relationship between conflict and progress.

Conflict and progress will also likely define the 21st century. Veterans of Israel’s Unit 8200 have founded scores of startups, including Palo Alto Networks, Waze, and Wiz. Combat in Iraq and Afghanistan contributed to significant medical advances, particularly the use of robotic prosthetics, and deepened our understanding of traumatic brain injuries. Facing a more powerful enemy, Ukrainians are developing long-range drones that cost $30,000 a piece (a fraction of the price tag for a cruise missile) to strike targets hundreds of miles inside Russia. On the battlefield, Russia and Ukraine are locked in an innovation race to produce tactical drones that start at $500. Prediction: By the time that war ends, delivery drones will be commonplace, and the best will come from Ukraine.

Hybrid Warfare

In a global economy, every point of connection is an axis of attack. Hybrid warfare is a conflict cocktail that blends conventional military operations, cyber, disinformation, guerilla tactics, lawfare, diplomacy, regime change, and economic warfare. Vladimir Putin is a seventh-level hybrid warfare wizard. He has covertly poured state resources into high- and low-tech means to pit Americans and Europeans against each other. Just as Big Tech realized the greatest ROI was misinformation from likable executives — “We’re proud of the progress we’ve made” — propaganda continues to be how nations punch above their kinetic weight class.

Radio Free Europe

The U.S. practices hybrid warfare, too. Radio Free Europe wrapped propaganda in rock & roll and pumped it into the Eastern Bloc. We spend $500 million a year so the Peace Corps can flex America’s soft power muscles. U.S. and Israeli computer scientists created Stuxnet, a virus that sabotaged the centrifuges at Iran’s nuclear facility without firing a shot. And despite spending $820 billion a year on kinetic power, our primary weapon of choice is economic. We lead the world in sanctions — it isn’t even close.

Unguarded

TikTok, owned by ByteDance, is a Trojan horse that enables the Chinese Communist Party to construct the frame through which American youth see the world, the U.S., and themselves. It’s not about whether the CCP strives to diminish U.S. standing and prosperity (they do), but if we should make it this easy for them. The U.S. government is slowly waking up to the TikTok threat. When it comes to communications platforms of declining influence — television and radio — U.S. law restricts foreign ownership. (Note: Rupert Murdoch bypassed this law by becoming a U.S. citizen.)

Investments affecting national security, energy, and infrastructure also face scrutiny. It’s a dumb idea to give your adversaries the ability to control your weapons systems, turn off the power grid, or close your ports. And it’s plain stupid to let them implant a neural jack into the wet matter of our youth. (See above: TikTok.)

American universities, however, are undefended — they are open for business. In 2019 fewer than 3% of 3,700 higher education institutions complied with a law requiring them to report foreign gifts or contracts exceeding $250,000. The following year an Education Department report concluded, “U.S. institutions are technological treasure troves where leading and internationally competitive fields, such as nanoscience, are booming. For too long, these institutions have provided an unprecedented level of access to foreign governments and their instrumentalities in an environment lacking transparency and oversight.” A subsequent crackdown has called into question foreign money at Harvard, Yale, MIT, and other schools. But Woodward and Bernstein, the Deadpool and Wolverine of journalism, didn’t just follow the money, they identified its source.

China

China

High tariffs keep Florida oranges out of the Chinese market. But contracts worth $1.8 million give Chinese growers access to University of Florida citrus research. One Florida grower called the deal an “intellectual property grab.” The University of Michigan has around $1 million in contracts from DiDi Global, a Chinese ride-sharing company built on government money that forced Uber out of their market. When a Chinese equipment maker filed an IPO, it told investors that its connection to the University of Minnesota allowed it to “enjoy the latest achievements of world-class R&D institutions.” Why worry about IP theft, when IP can be purchased at a deep discount on campus?

Saudi Arabia

Sixty-two U.S. universities receive billions from Saudi Arabia. In exchange, the Saudis get access to America’s top minds, but they also get a brand makeover. The Kingdom has made similar investments in sports and startups, including in Premier League football, the PGA, and WeWork. This is, in my view, a market transaction that’s good for both parties, as American firms get access to cheap capital. However, there’s something uncomfortable about a monarchy that doesn’t share our values having influence over the universities that, arguably, shape the values of tomorrow’s business and government leaders.

A former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia likened the Kingdom’s “higher-ed-washing” campaign to U.S. soft power. True, it’s the same tactic, but there’s no moral equivalency. When the Saudis buy brand makeovers from American universities, there is also a risk that the curriculum and professorships will question, in the most civilized manner, our American values.

Qatar

Since 1998, Qatar has spent billions funding satellites of U.S. universities in Doha. “Education City” is home to campuses for Georgetown’s school for politics and foreign relations, Carnegie Mellon’s computer science department, Virginia Commonwealth’s fine arts department, Cornell’s medical school, and Northwestern’s journalism school. Texas A&M has an engineering school in Qatar, though it’s set to close in 2028. Why? School officials say they’re concerned about stability in the Middle East. Meanwhile, a think tank known as the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy alleged that Qatar had “substantial ownership” of weapons development rights and nuclear engineering research being developed at the Texas A&M campus. Texas A&M denies the allegation.

Nations form alliances and partnerships based on shared interests, not altruism or friendship. This is the reality of geopolitics and our relationship with Qatar — it’s got an awful human rights record and ties to Hamas and Iran, but it’s also home to the largest U.S. military base in the Middle East. It’s complicated.

American foreign policy needs Qatar; American universities don’t. Elite schools enjoy endowments worth billions and charge students roughly the equivalent of a luxury car for every year of tuition — they might miss Qatar’s money, but they don’t need it.

Patriotism

Nearly 300 UCLA graduates gave their lives during World War II. My alma mater isn’t unique. U.S. colleges coast to coast mobilized for war. Every school sent graduates to the front lines. The University of Maryland graduated students in three years to boost enlistment. Columbia University changed its curriculum to serve the war effort. By 1942 as many as 3,000 armed forces personnel were taking classes at Harvard. And, of course, America’s research universities provided the intellectual firepower, including the atomic bomb, that won the war. The Greatest Generation displayed a sense of duty and patriotism that we applaud today as exemplary. Their love of America helped them save America.

We’re less patriotic today, especially young Americans. That should be a clear and present danger to university administrators and faculty as autocrats threaten democracy in the U.S. and around the world. We armed the Greatest Generation with patriotism; we’re disarming today’s students with narcissism.

Tip of the Spear

Universities are the tip of the spear for America, shaping the next generation of leaders and innovators. Our purpose is to provide an environment where students can explore their passions, challenge their beliefs, and develop critical thinking skills. Trashing America might earn students and faculty clout online, but in the real world it’s stupid. (UC Berkeley Professor Carlo Cippolla identified “stupid” as people who hurt others while hurting themselves.) We’re on the road to stupid, and it’s paved with money from our adversaries.

Americans’ superpower is our optimism. However, the Achilles’ heel of this optimism is that it’s easier to fool Americans than convince them they’ve been fooled. This, coupled with money-obsessed, bloated universities have turned American values of intellectual freedom and free speech on itself. Cancer is when the host’s own cells turn on it, and America’s cancer is the coarsening of our discourse and the emergence of a white-hot fashion among university youth — hating America. Is the $14 billion that has poured into American universities an attempt to build bridges between us and other nations, or is it a long game being played by our adversaries to turn our cells (youth) against us? The answer is yes.

Is there a point where the risks outweigh the upside? As someone who’s given money to universities, I know that, no matter how benign, the donor expects something in return (e.g., influence over curriculum, who receives financial aid, faculty hires).

Campus leaders need to ask a simple question: What do foreign nations want in return for their billions, and what are they getting?

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. This week on Prof G Markets, Mark Mahaney, senior managing director and head of internet research at Evercore, joined me and Ed to discuss why the market’s freakout is an opportunity, not a crisis. Listen here on Spotify or here on Apple Podcasts.

P.P.S. Section released new research: The AI Proficiency Report. It finds that only 7% of people are really good at using AI — the rest of us need to catch up. Download here.